When those previously not in the know suddenly are, it’s not questions from aspirational figure skaters that immediately follow for Cati Snarr.

It’s requests. A bombardment of requests. That’s what happens when you spent several years teaching one of America’s next figure skating superstars.

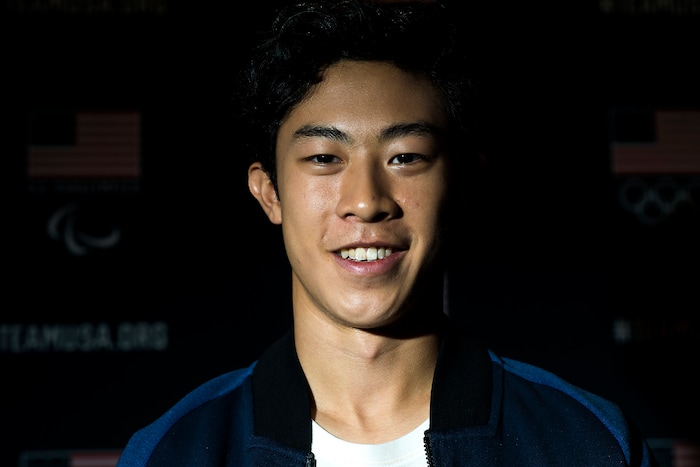

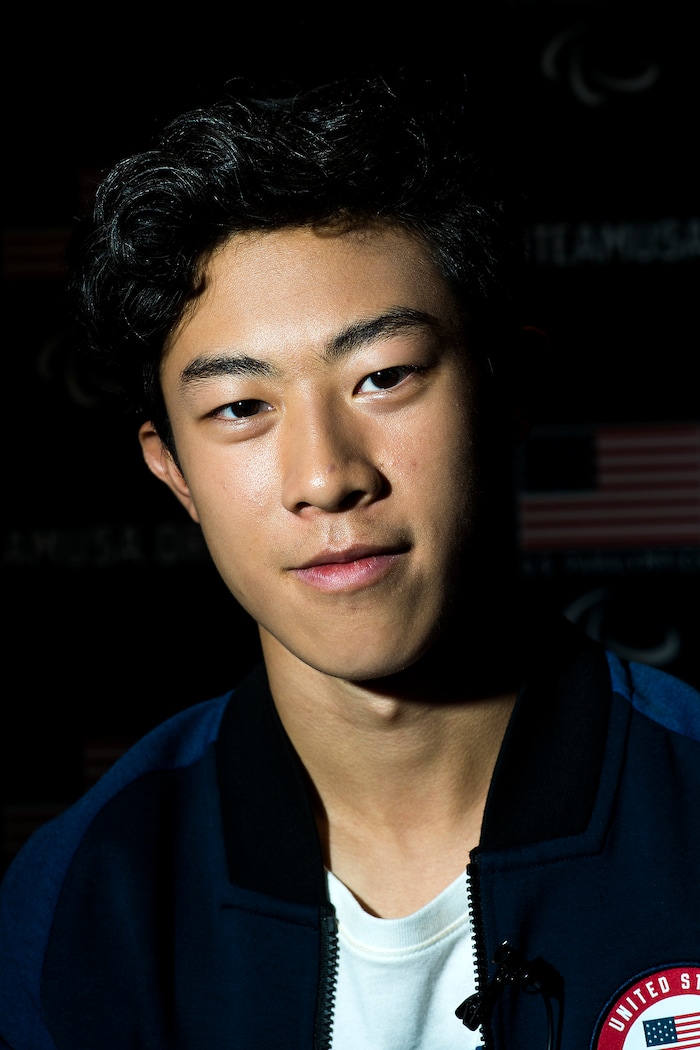

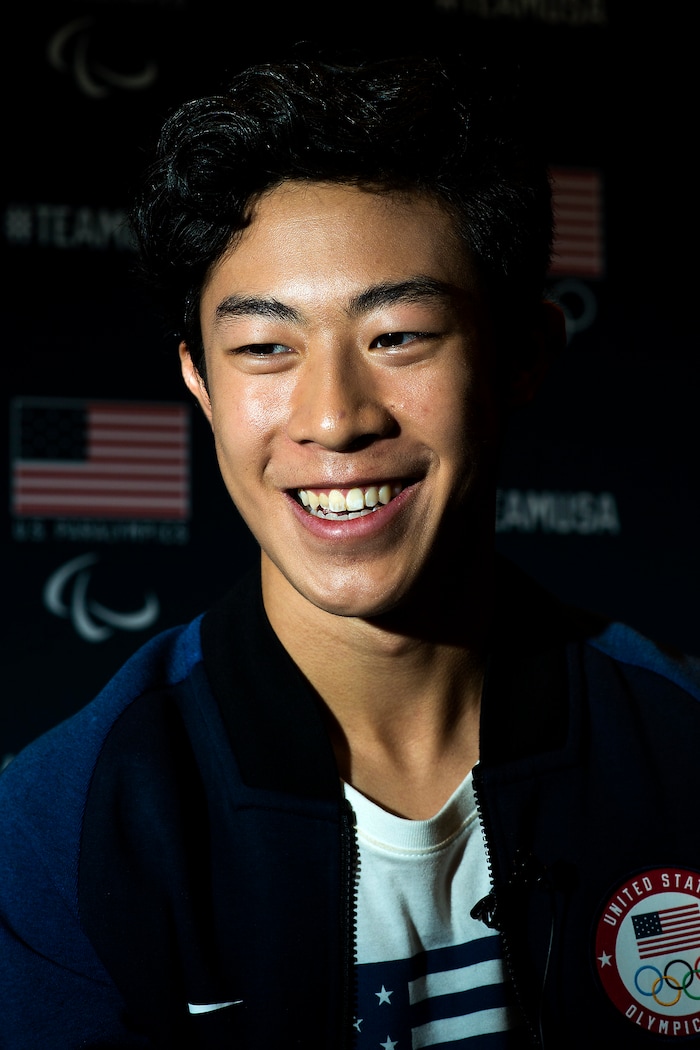

Snarr instructed Nathan Chen in ballet, and considering that the 18-year-old has captivated the Olympic realm so swiftly and confidently — like one of his many quad jumps on the ice — figure skaters gravitate to her hoping for a similar trajectory.

“Skaters are coming out of the woodwork,” said Snarr, now the principal at Ballet West’s Park City academy. “They’re all saying, ‘I need ballet classes!’ It’s created value in the sport, and it wasn’t like that before.”

Snarr calls it “such a beautiful extreme.”

It’s a description that also appropriately encapsulates Chen, one of her former pupils. Born and raised in Salt Lake City, he now is the two-time defending U.S. national champion who as a 10-year-old novice skater once publicly proposed that these 2018 Olympic Winter Games would be where he’d eventually make his debut.

But between his advancement on the ice, gymnastics and hockey, an unmissable part of Chen’s rise in the sport that remains a chief draw at a Winter Games was his six years at Salt Lake City’s prestigious Ballet West Academy.

Snarr recalls what many still hold onto as their first impression of Chen: a shy, undersized, highly motivated youngster with an uncanny ability to fixate on assessing the minor mistakes made in classes or performances and making corrections.

And like skating, he always could launch himself off the floor and spin. From Day 1. It was one of the first steps to becoming the “Quad King” as he’s being marketed heading into these Olympic Games.

“He is 180 degrees turned out, that kid,” Snarr said. “He goes up, turns his legs, squeezing everything together and he automatically has balance and torque. He’s turning because he can’t even help it. It’s not even about force. It’s not even about always fighting gravity because he has all those other things and natural flexibility.”

“He had such mastery of his body,” said Peter Christie, Ballet West’s former academy director who is now the education and outreach director.

Perfect finish

Hetty Wang dropped off her son after school five days a week at Ballet West’s studios in downtown Salt Lake City. This was after Chen arose in the wee hours every morning to hit the ice at 5 or 6 a.m. so he could practice and train on his own. Chen and other academy students went through 90-minute sessions.

Snarr and Christie realized from the outset that Chen was exceptional.

“You’d have kids backstage who wanted to goof around,” Christie said, “and he was watching, analyzing, watching performances and focusing on what’s happening.”

For all his physical tools and attention to detail, Chen needed to be taught how to command a stage. His teachers say embracing different roles in various productions helped. The young extrovert had to shift out of his own mentality and become Fritz, a mischievous character in “The Nutcracker.” While he tried to perfect his moves, Christie said they worked on projecting characteristics out of Chen, which has gone a long way in expanding his gravitas on the ice.

Instead of owning the character in front of his teachers or those in the first few rows of the theater, they told him he must perform for the person farthest from the stage. It took some time, but now, when Snarr and Christie tune in to one of Chen’s programs on the ice, they notice how he glances to the top of whatever stadium or building he’s competing in. Showmanship, it turns out, was one of the last pieces to his mastery as a prodigal talent.

“It became about projection,” Christie said, “and going back to how thoughtful he is and how much goes on in his brain. It doesn’t translate out in the physical, so [he had] to exaggerate to the rafters of the arena you’re in.”

The late Mark Goldweber, who served as ballet master at Ballet West, once requested Chen perform a tour — slang for a 360-degree spin in ballet. When Chen came down in perfect form, Goldweber asked if he could do two in a row as flawlessly.

Up Chen went on back-to-back spins.

“Perfect finish,” Snarr remembers. “He wasn’t afraid to try things, too, which went to his benefit.”

Photo courtesy Ballet West/Luke Isley: Nathan Chen (right) in his role during a 2011 production of "Sleeping Beauty."

Goldweber eventually created a character and performance variation in “The Sleeping Beauty” just for Chen, which allowed him to show off his distinct abilities in the air. No ballet dancer at the academy had developed so quickly such prowess for spinning like Chen, who started at Ballet West at age 7.

“Not to the clarity that he had,” Snarr said.

Chen performed about one or two full-time roles each year during his time at Ballet West. In all, he had five roles before the Chens left Salt Lake City and relocated to Southern California when he was 12 so he could train more closely with his figure skating coaches.

Still, male company dancers who remember Chen as a young academy dancer have told Christie and others that if he ever wanted to, he could return to ballet and pick it up without missing a beat.

“For sure,” Snarr said, “no problem.”

‘This is really happening’

(Chris Detrick | The Salt Lake Tribune) Nathan Chen greets members of the crowd after winning the Men's Free Skate during the U.S. International Figure Skating Classic at the Salt Lake City Sports Complex Friday, Sept. 15, 2017.

Chen, back in his hometown last September, visited the Capitol Theatre and the Ballet West studios for a report on NBC News. In Salt Lake for the first official competition of his 2017-2018 season, he said: “This is where it all started. My training and ballet background definitely gives me the competitive edge on the ice.”

Chen, of course, later won the 2017 International Figure Skating Classic last fall in runaway fashion on the ice that he learned to skate on at the Salt Lake City Sports Complex.

Snarr was there in the crowd. Afterward, Chen weaved through what she described as “a sea” of female teenage superfans to embrace his former teacher. When Chen snagged Bridgestone tires as one of his primary sponsors, she saw him advertised front-and-center at a local tire store, took a photo and sent it to him.

“Look at you!” it read.

It was a personal cap to a story they’d seen coming firsthand for the better part of a decade.

Surprised?

“Not at all,” Christie said. “In our vocabulary, it was, ’When you’re at the Olympics.’ We saw all the evidence going into competitions and him winning everything.”

Snarr and Christie also helped choreograph portions of the Opening and Closing Ceremonies at the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City. Ballet might be their forte, but being involved in the Games in Utah 16 years ago got them hooked. Now they do their best to manage their nerves watching Chen.

Snarr holds her breath when he picks off the ice to execute one of his history-making quad jumps. No skater ever has done more high-risk spins in a program than Chen, which he’ll do once more at these Games with gold in mind. So when he takes off, she sees the young boy who listened to Goldweber’s request, to his nights as young Fritz, to the special program installed for his ability to spin onstage, all of which helped him master the litany of quads and own the spotlight.

She also screams corrections through the TV.

So many mentors in various sports or arts have helped Chen get to this point, each instilling a dash of versatility that has made him America’s next great star skater. In a conference room inside the Capitol Theatre, Snarr and Christie can’t help but feel the weight of the moment for Chen’s first skate at the Gangneung Ice Arena in South Korea.

“This is really happening,” Christie said, shaking his head.

“I’m going to get a therapist,” Snarr said. “I can hardly stand it. I can hardly move.”