Hamburg, Germany • Helmuth Hübener became a political dissident in Hitler’s Germany by reading banned books, listening to censored broadcasts, and imbibing Mormonism’s teachings about truth and consequences.

Ultimately, Hübener paid with his life for his efforts to expose the dishonesty and dangers of the Nazis.

The 17-year-old was beheaded 82 years ago this week, on Oct. 27, 1942 — the youngest “resistance fighter” to be executed by the regime for treason — and, ironically, was listed as “excommunicated” from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which had provided the foundation of his faith.

After the war, the boy’s membership was quickly restored and eight decades later, Hübener’s heroism is heralded by the Utah-based church itself, which has participated in celebrations of the young Latter-day Saint and relayed his story on its website.

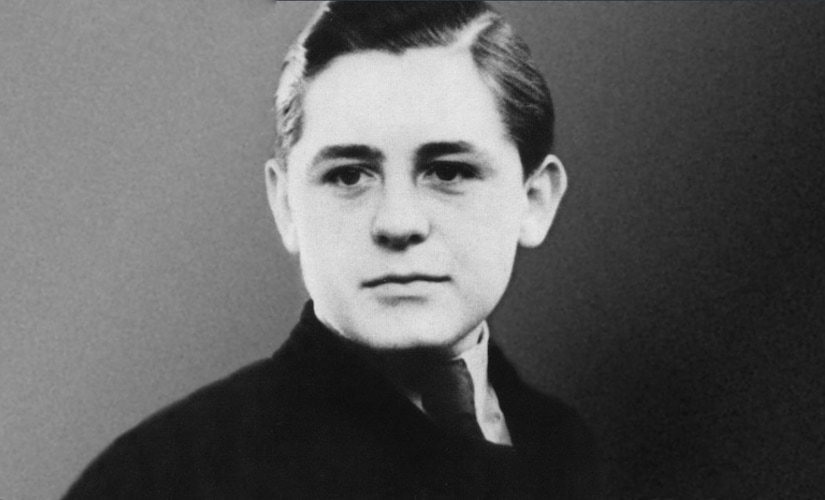

(Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand) An undated photograph of Helmuth Hübener.

The German teen has been the subject of articles (Sunstone magazine, “The Fuhrer’s New Clothes” in 1980), a play (Thomas Rogers’ Hübener in 1976), books (“The Price” in 1984, “Before the Blood Tribunal” in 1992 and “When Truth Was Treason” in 1995), a documentary film (“Truth and Conviction” in 2002) and a forthcoming feature film by the same name.

Memorial exhibits have been installed at a vocational school in Hamburg, at the German Resistance Memorial Center in Berlin, and at Plötzensee Prison, where Hübener was executed. On top of that, two streets in Hamburg, a youth center and a school bear his name.

(Michael Stack | Special to The Tribune) A alleyway named after Helmuth Hübener in central Hamburg, Germany, May 12, 2024.

(Michael Stack | Special to The Tribune) The Plötzensee Prison in Berlin, May 10, 2024, where Helmuth Hübener was held and executed.

Most recently, a school associated with Berlin’s youth correctional facility was named for Hübener, and the curriculum is based on his life and works. Its motto, taken from his name, means “make it a practice to act with courage.”

“As a teenager, I had a poster of my favorite soccer team and a framed photo of Helmuth Hübener on my bedroom wall. Today, I have pictures of my grandson and of Helmuth Hübener on my desk at the office,” says Ralf Grünke, a third-generation Latter-day Saint in Germany and a church spokesperson for Central Europe. “Helmuth’s example of courage and uprightness guided me through the journey of my formative years and beyond. At a time when hatred toward minorities and warmongering became guiding principles of government and society, he held onto the maxim of [the hymn] ‘do what is right; let the consequence follow.’”

Without his inspiring story, Grünke says, “I wouldn’t be where and who I am today.”

(Michael Stack | Special to The Tribune) Ralf Grünke, assistant communications director for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Central Europe Area, in Hamburg, Germany, May 13, 2024. Helmuth Hübener’s story played an important role in Grünke's development as a young Latter-day Saint.

To be clear, not all German Latter-day Saints were on the side of righteousness during World War II.

Some were Nazis, who arrived at church in their uniforms and derided other members about their associations and politics (like destroying an Allied pamphlet that a member had innocently picked up), Hübener biographer Alan Keele says in an interview. Some were quiet opponents of the regime, who helped and harbored Jews. But most were somewhere in between — keeping their heads down and hoping they (and their American church) would survive the war at all.

It was, well, complicated.

“In my view, we can and must find a way,” Keele, an emeritus Brigham Young University professor of German studies, writes in an unpublished essay, “to learn from all of them, from the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

Growing unease

Hamburg’s little St. Georg [sic] Latter-day Saint branch, which Hübener attended with his grandmother and two brothers, reflected the German society around them.

The congregation’s president, Arthur Zander, was a Nazi Party member “who compelled branch members to listen to the party’s radio broadcasts, threatened to report members for anti-government activities, and, in 1938, posted a sign on the meetinghouse door informing Jews they were not welcome,” according to the church’s online essay. “A handful of members wore their Nazi military and civil service uniforms to church meetings.”

(Werner Sommerfeld) A group photo of Latter-day Saint members from the Hamburg, Germany, St. Georg branch, which Helmuth Hübener attended in the late 1930s.

Meanwhile, Otto Berndt, the Hamburg district president (who oversaw a number of Latter-day Saint congregations) “preached against government policy from the pulpit, privately encouraged member resistance, and frequently walked with Jewish converts.”

Young Helmuth was a good student, who spoke fluent English, loved music, and was skilled in stenography, writes biographer Keele. After leaving school, he began an apprenticeship with the civil service, where he had access to the administrative archives and books the Nazis had banned.

Then, in 1941, he found a shortwave radio belonging to his older brother and, in defiance of Nazi law, tuned in to BBC broadcasts, describing what was happening in Germany.

He soon grew “convinced of the wrongness of the Nazi program,” Keele writes, “and decided that he must actively oppose it.”

Armed with branch typewriters and carbon paper to produce anti-Nazi leaflets, Hübener enlisted two young friends from the congregation, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe and Rudolf (Rudi) Wobbe, to help him distribute them. He approached a work buddy, Gerhard Düwer, at the Hamburg Social Authority to help as well. Over about eight months, he wrote and distributed hundreds of leaflets.

In one of them, he attempted to show that his opposition to the Third Reich came from his Latter-day Saint faith, Keele writes, expressing “naive confidence in the basic goodness and educability of mankind,” and in the “eventual triumph of good over evil.”

By 1942, though, Gestapo agents were onto the scheme and arrested the four teens on various charges, including “conspiracy to commit high treason.”

Hübener, who took responsibility for the whole plan, was sentenced to death, while Wobbe, Schnibbe, and Düwer, were sent to labor camps.

Just before meeting the guillotine, Hübener wrote a letter to Marie Sommerfeld, a member of the Hamburg branch. There are no copies of the letter, Keele says, but the young woman committed it to memory.

It reads in part: “My Father in Heaven knows that I have done nothing wrong. …I know that God lives, and he will be the proper judge of this matter. Until our happy reunion in that better world, I remain your friend and brother in the gospel, Helmuth.”

A fearful faith

On the Sunday after the arrest, Karl, Rudi, Hübener’s mother and grandmother all attended the St. Georg branch, Keele reports, where they heard a branch member say: “I’m glad they caught him. If I’d known what he was doing, I’d have shot him myself.”

Shortly after Hübener’s arrest, Zander, the branch president, wrote “excommunicated” on Helmuth’s membership record, the church essay explains. When Berndt, the district president, refused to co-sign the action, Anthon Huck, a member of the West German Mission presidency, provided a second signature.

“Several church leaders later said they intended to distance the church from Hübener,” the essay asserts, “to protect Latter-day Saints from the wrath of Nazi officials.”

(Werner Sommerfeld) Arthur Zander, the Latter-day Saint branch president who, shortly after Helmuth Hübener’s arrest, wrote “excommunicated” on the teen's membership record.

(Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand) A proclamation from the Special People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof) announcing Helmuth Hübener’s execution on Oct. 27, 1942.

It was a scary time for church members as they tried to navigate their survival in Hitler’s Germany.

Some German Latter-day Saints “who would have given their lives for the gospel,” Keele writes, “believed that Hübener was a heretic, for he had violated the Twelfth Article of Faith…about being subjects to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates.”

Plus, they got no direction from church headquarters in Utah, where then-President Heber J. Grant urged German members to stay in the country and try to keep building the faith.

The German Saints were “not eager for a confrontation with their national government,” Keele says. “By and large, the Mormons and the Nazis coexisted comfortably. Some church members even saw Hitler as God’s instrument, preparing the world for the millennium.”

And they knew they were being watched.

After Hübener’s arrest, Berndt was questioned by officials.

“Make no mistake about it, Berndt,” the investigator told him, according to Keele. “When we have this war behind us, when we have the time to devote to it and after we have eliminated the Jews, you Mormons are next.”

Werner Sommerfeld, Marie’s son, was 11 years old when Hübener was killed.

“There was no communication between headquarters and the branch,” recalls Sommerfeld, who turns 95 this month. “All the brethren [male leaders] who were called as branch leaders acted on their own.”

(Michael Stack | Special to The Tribune) Werner Sommerfeld, a childhood associate of Helmut Hübener and fellow member of the Latter-day Saint St. Georg branch in Hamburg, Germany, at his home in Millcreek on June 20, 2024.

For his part, the elderly German living in Millcreek doesn’t blame Zander, who, he says, “wanted to protect the church.”

But Sommerfeld does feel bad about Salomon Schwartz, a Jewish convert, who died in Auschwitz after being blocked from attending Latter-day Saint services.

‘A trap for believing people”

Political movements like Germany’s National Socialist Party “pose a trap for believing people by pretending to stand on moral high ground,” Keele writes. “They appear to oppose all the ‘immorality’ of their times, which believing people instinctively loathe, thus luring the unsuspecting faithful into their snare.”

Helmuth Hübener and his co-conspirators “apparently managed to land on the right side of this historical spectrum,” he concludes, “whereas the actions of their branch president, Arthur Zander, a fervent member of the Nazi Party, are today an acute embarrassment.”

During a recent visit to Auschwitz in Poland and Plötzensee Prison in Berlin, Latter-day Saint apostle Dieter Uchtdorf, says on Facebook he “was reminded of the atrocities that can occur when we fail to love one another as brothers and sisters.”

Uchtdorf, the only German apostle, placed a bouquet of flowers at the prison, moved by the story of the 17-year-old Latter-day Saint who gave up his life for the truth.

Sommerfeld, the oldest living Latter-day Saint who knew Hübener, is surrounded in his Utah home by photos, news accounts of the war and memorabilia from that time.

The lively senior doesn’t need flowers to remind him of that boy’s sacrifice. He cannot forget.

Editor’s note • This story is available to Salt Lake Tribune subscribers only. Thank you for supporting local journalism.