St. George • Many experts agree that four mass burial sites are the final resting places of most members of a California-bound emigrant wagon train from Arkansas who were slaughtered in 1857 by Latter-day Saint militia members at Mountain Meadows, about 35 miles northwest of St. George.

The number of graves could increase, however, if an investigation of three rock piles recently discovered adjacent to the Mountain Meadows Massacre site pans out. But the prospect that any of the new sites hold the remains of some of the roughly 100 men, women and children who were executed — many at point-blank range — is dubious.

Historians and archaeologists remain skeptical but say it is possible that one or more of the three cairnlike piles might contain graves linked to the horrific assault, the bloodiest stain in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ Latter-day Saints.

“The church is going to take a very conservative approach here,” said archaeologist Ben Pykles, director of historic sites for the Utah-based faith, which now owns the property. “We’re going to treat them as graves — not necessarily Mountain Meadows graves — and we are going to protect them.”

The Arkansas wagon train was en route to California when it stopped at the meadows and was attacked by militiamen and their Paiute allies. On Sept. 11, five days into the standoff, militia member John D. Lee, acting under false pretenses, waved a white flag and secured entrance to the encircled wagon fort.

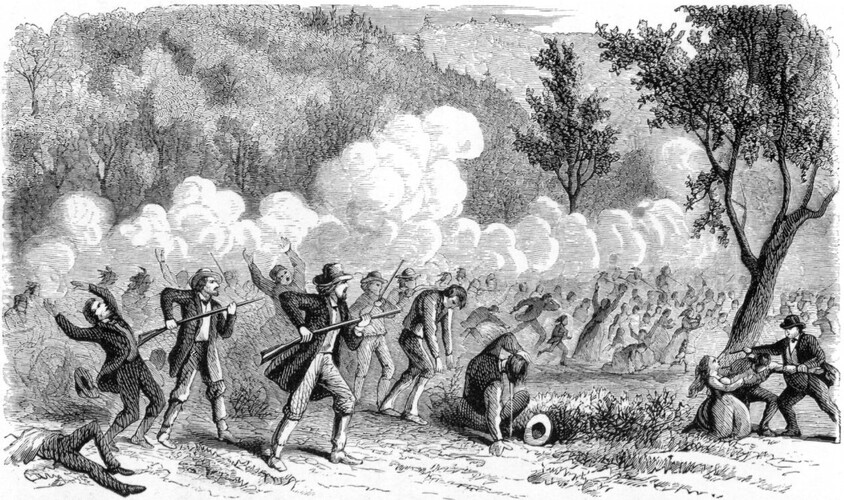

(Stenhouse) A depiction of the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Once inside, Lee convinced the emigrants that the militia would guarantee them safe passage if they laid down their arms and came out. Reassured by the Latter-day Saint leader’s false promises, the emigrants surrendered their weapons and emerged, walking in single file. About a mile into the march, at a prearranged signal, the militiamen killed the men, women and children.

Only 17 kids, age 6 or younger and deemed too small to remember the atrocity and its perpetrators, were spared.

Burying the dead

Historical records show that most of the victims were interred in four graves. In spring 1859, more than 18 months after the massacre, U.S. Army Capt. Reuben Campbell and his troops camped at Mountain Meadows, where he ordered surgeon Charles Brewer and a detachment of soldiers to bury the dead.

Barbara Jones Brown, co-author with Richard E. Turley Jr. of “Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath,” said Brewer and the soldiers found eight skulls and other bones near the site of the siege and buried them at the base of a nearby hill, the precise location of which is unknown.

(Chris Samuels | The Salt Lake Tribune) Richard E. Turley, left, and Barbara Jones Brown, the authors of “Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath.”

About 2,500 yards to the northwest, the surgeon and the soldiers found and reburied other skulls and bones protruding from an apparent mass grave in a ravine that Brewer concluded were the remains of the men and older teenage boys who were killed.

Some 350 yards away, according to historical records, the soldiers found the remains of the women and children partially covered with a thin layer of dust or earth, which they buried in a third mass grave.

“I believe [the women and children] were left to lie on the ground,” Brown said, “because the militiamen wanted this to look like an Indian massacre.”

Both the second and third burials sites were marked with rock piles that were lost to history until archaeologist Everett Bassett ostensibly rediscovered them in 2015. Without exhuming the remains and conducting DNA tests — which neither church officials nor the descendants of the massacre victims want — it is impossible to determine with absolute certainty if the two sites actually contain the remains of the men and older boys and women and children. Extensive analysis of the historical record and other evidence, however, has led to a consensus from most experts that the archaeologist was spot-on.

In May 1859, a fourth mass grave was created at the direction of Maj. James Henry Carleton, who rode with his troops out of Fort Tejon in Southern California. Upon arriving at the killing field, he commanded soldiers to gather up all the bones strewn across the valley — including some that pioneer Jacob Hamblin, a nonparticipant in the massacre, had found and interred the previous summer — and rebury them.

Carleton’s men entombed the remains of at least 30 victims at the siege site, atop which they emplaced a conical-shaped cairn monument with a cedar cross rising out of it, on which they inscribed the biblical verse “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.”

That monument underwent several revisions through the years due to weather, erosion and vandalism. In 1999, the church replaced the original monument and a 1932 memorial wall with the current graveside memorial, which consists of a cairn encircled by a sturdy stone wall and metal fence over which the U.S. and Arkansas flags fly.

To preserve and protect

(Mark Eddington | The Salt Lake Tribune) The site of the Mountain Meadows Massacre on Monday. Dec. 4, 2023.

In 2022, the owner of some nearby land informed the church of a rock pile on his property that resembled the cairns that Bassett had discovered. Upon examining the rocks, and in consultation with massacre descendants, Pykles and his colleagues opted to survey the entire area — both the private landowner’s and church property — to look for other possible graves.

A company with a drone using Light Detection and Ranging, or lidar, technology was employed to identify possible burial locations. Afterward, the church hired California-based Institute of Canine Forensics to comb potential graves with cadaver dogs specially trained to find human remains.

Pykles said the dogs found three potential locations. One of the two located on the landowner’s property is more prominent than the other. He said the third, on church land, was also substantial but looks different than the other two. He said the church has since purchased the private property, just as it did with the two burial sites that Bassett discovered.

In September, Pykles and his colleagues met with representatives of the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation, Mountain Meadows Association and Mountain Meadows Massacre Descendants to show them the three possible graves.

“We are excited about the possibility that more graves have been discovered and to know where to go from here,” said Phil Bolinger, president of the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation.

Precisely what direction that may be is uncertain.

“All we know,” Pykles said, “is that the dogs smelled human remains. The dogs don’t tell you who they are smelling.”

(Utah State Historical Society) John D. Lee, seated at left in the above image, poses next to his coffin before his execution in 1877. The bottom illustration is from Frank Leslie's "Illustrated Newspaper" showing the execution of Lee for his role in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

Mountain Meadows rests on the Old Spanish Trail, a popular thoroughfare for pioneers, forty-niners and others making their way between what is now Utah and California.

“Indigenous people have inhabited the area for generations,” author-historian Barbara Jones Brown said. “So the three [sites] could be burials for Paiutes or any number of travelers who passed through … It doesn’t mean they are Mountain Meadows graves.”

Unlike the other burial locations, there is nothing in the historical record about the three new rock piles. Nonetheless, Pykles believes it is possible one or more of them could be linked to Mountain Meadows. Patty Norris, president of the Mountain Meadows Massacre Descendents and who often visits the site, believes at least two of them could be massacre graves.

“I’m blood-connected to most of the massacre victims, so visiting the site is always an emotional experience for me,” said Norris, great-great-granddaughter of Capt. Alexander Fancher, who was slain along with his wife, Eliza, and seven of their nine children at Mountain Meadows.

Conversely, Bassett believes the two rock piles on the land the church just purchased resemble “check dams” more than cairns. He said the Utah Road Commission might have erected small dams in the 1930s while building State Route 18 to prevent water erosion from a gully leaching onto the road. He is uncertain about the third, differing, rock pile.

(Mark Eddington | The Salt Lake Tribune) The site of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in southwestern Utah on Monday. Dec. 4, 2023.

“If I went out and spent four or five days surveying everything within two miles of that location,” Bassett said, “I could probably find 10 or 12 piles of rock that look kind of like these … These three happened to be close to where the massacre took place. But as far as I’m concerned, that’s about the only thing that characterizes them as being different than all the others.”

For her part, Brown leans more toward Bassett’s interpretation.

“As historians and archaeologists,” she said, “we don’t want [the three rock piles] to become part of the historical narrative and for people to say they are graves of massacre victims because we just don’t know.”

Wherever the truth may lie, the church has decided it is better to err on the side of caution. To that end, Latter-day Saint officials are safeguarding the possible graves and not disclosing their location.

“We are focused on protecting and preserving them,” Pykles said, “regardless of whose bones lie beneath.”

Editor’s note • This story is available to Salt Lake Tribune subscribers only. Thank you for supporting local journalism.