In settling on the subject of her latest book, historian Eileen Hallet Stone decided not to write about Utah’s historic ghost towns that other writers have thoroughly explored. Nor did she want to stick to the “faith in every footstep” narrative that prevails in most discussions of the state’s frontier past.

She opted instead to write about Utah’s more unsavory history — about the unofficial church photographer who took pictures of Latter-day Saint prophets and apostles while trafficking in selling photos of scantily clad women on the side; about the working girls who plied their illicit trade beneath trees, in covered wagons or in upscale bordellos; and about the corrupt lawmen and pious Utahns who pilloried and profited off of the women.

The result is her latest offering from South Carolina-based History Press, “Selling Sex in Utah: A History of Vice.”

Skirting Brigham’s disapproval

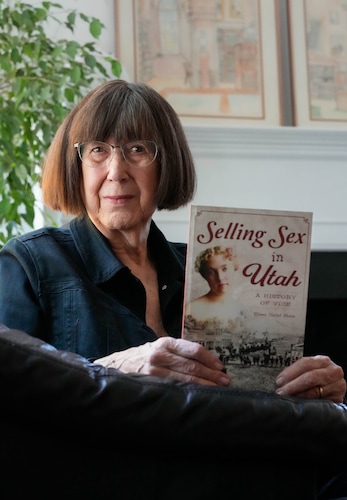

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) History writer Eileen Hallet Stone has a new book out titled "Selling Sex in Utah: A History of Vice,” as she sits for a portrait and talks about the world’s oldest profession and Utah’s more unsavory history on Wednesday, July 12, 2023.

In researching and writing about prostitution, Stone has unearthed colorful stories that spotlight the state’s less-flattering past. Among the gems she has mined is an account of the first ballet held at the Salt Lake Theatre, which was built in 1861 at a cost of $100,000.

According to an account of the event by Brigham Young University historians Kenneth Alford and Robert Freeman, which Stone relates in “Selling Sex,” pioneer prophet Brigham Young insisted the ballerinas’ skirts be ankle-length, prompting their manager to lament that would make it impossible for them to dance.

Sure enough, many of the dancers “tripped and fell” over their long skirts during the ballet. Before the second performance, the manager shaved an inch off the skirts. When that went unnoticed or ignored by Young, the manager shaved off another inch every successive performance — all of which the church leader attended — until the skirts were at their original length.

(Tribune file photo) Brigham Young, second president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Early Utahns, largely members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and their preference for lowbrow entertainment, raised the eyebrows and hackles of church President Joseph F. Smith.

“When we get high-class performances in that [Salt Lake] theatre, the benches are practically empty,” Stone quotes Smith as saying, “while the vaudeville theatres, where there are exhibitions of nakedness, of obscenity, of vulgarity and everything else that doesn’t tend to elevate the thought and mind of man, will be packed from pit to dome.”

Church photographer and purveyor of erotica

(Utah State University Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections) Pictures taken by Charles Ellis Johnson, who photographed Latter-day Saint leaders and scantily clad women.

Perhaps few risked incurring church leaders’ wrath as much as Charles Ellis Johnson, the Salt Lake City cameraperson who emerged as the faith’s unofficial photographer. When he wasn’t taking pictures of Latter-day Saint leaders and temples, he was shooting portraits of “scandalous burlesque” and women in various states of undress.

Johnson married Ruth, one of Brigham Young’s daughters in 1878. When she abandoned him and took their two sons to California, the photographer carried on with his craft. By the turn of the century, Stone writes, Johnson’s photos became more “brazen and began showing … partially nude women baring garters, stockings, uncovered shoulders, thighs, semi-transparent clothing and half-exposed breasts.”

(Photograph courtesy of the Special Collections, Merrill-Cazier Library, Utah State University) The famed Salt Lake City photographer Charles Ellis Johnson, the unofficial church photographer who took pictures of Latter-day Saint prophets and apostles while trafficking in selling photos of scantily clad women on the side, ran his studio next to the temple.

Johnson peddled his wares at his studio and wrapped the more risque photos his customers purchased in plain paper as they exited the premises. He also opened a mail-order business, trafficking his erotica across state lines and oceans to foreign countries.

“It’s a wonder,” Stone said in an interview, “he wasn’t caught mailing images that were considered obscene and illegal in that day.”

Johnson’s business and secret sales violated the Comstock Law of 1873, which made it illegal to send obscene materials through the mail or to sell or give away salacious books, pamphlets, pictures and ads.

A risky and deadly business

(Western Mining and Railroad Museum) A model of a brothel room in Helper.

Anecdotes about ballet and photography in “Selling Sex” make for interesting diversions. The bulk of the book, however, deals with prostitution, which thrived with the arrival of miners and railroad workers to the Latter-day Saints’ Zion.

As Stone describes it, prostitution in frontier Utah was more squalid than sexy or glamorous — and it was dangerous. Hygiene was often in short supply. So were women’s contraceptives — the sale, distribution and information about which was illegal due to the Comstock Law.

And what little medicine was on hand — typically mercury and arsenic — was more apt to kill than cure those afflicted with venereal disease. The author recounts a popular adage of the times: “A night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury.”

In her book “Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains,” author Jan MacKell Collins wrote that in 1874 an estimated 1 in 18.5 people in the United States had syphilis and roughly half the prostitutes in mining towns were afflicted with the disease for which there was no cure at the time. Stone said working girls often were raped and suffered other forms of physical violence and cruelty.

“The attitude about women, especially prostitutes, was almost like they were nothing, only existing to be used,” she said. “If they were raped, how could they say anything about it? They were prostitutes. Who is going to believe them?”

Stone said prostitutes arrived in Utah for a variety of reasons. Some were escaping domestic abuse or had been widowed or divorced and left destitute. Others took to the trade for fun and adventure or to find a husband.

Fighting the law and injustice

(Via Steven Lacy) Three prostitutes in a brothel in Carbon County.

When it came to dealing with injustice, the author said, many of the women preferred fighting to fleeing. A case in point is Kate Flint, a madam who ran brothels in Salt Lake City’s red-light district on Commercial Street, now known as Regent Street.

Police raided Flint’s home in 1872. She was found guilty and fined. When Flint appealed her fine, Stone wrote, Judge Jeter Clinton responded that he could not make out an appeal bond until the city attorney returned, but he assured her she could return home and nothing would happen until the morning.

Stone said Clinton was lying. He had already declared Flint’s home a public nuisance and ordered the “church-dominated police force” and Latter-day Saint businessman Brigham Young Hampton, a onetime constable and a bodyguard for Brigham Young, to abate her residence.

When Flint arrived home, it was in pieces. All the furniture was smashed or kicked in, and Hampton was rifling through the contents of her bureau when she entered her room. A wad of cash was also missing.

When critics railed against the judge and his court-ordered “illegal” abatement, the church-owned Deseret Evening News rallied to his defense, saying the sentiment of the vast majority of Utahns “still desire their sons to be husbands, not paramours, their daughters to be wives, not harlots.”

Conversely, The Salt Lake Tribune countered with a blistering attack on the judge and the polygamous City Council and police court.

“The lascivious evils of Commercial Street have never equaled the lasciviousness of marrying mother and daughter, two sisters, or many other of the abominations of polygamic intercourse,” The Tribune stated, “yet this species of licentiousness is called religion.”

Not one to be cowed, Judge Clinton fired back at his critics in a sermon reprinted in the Mormon Expositor.

“The Jews and the gentiles have driven us from place to place, and they have tried to drive us out, but I can tell you, friends, that we are not going from here … Now for these women, the low, nasty streetwalkers … the low, nasty, dirty, filthy, stinking [expletive deleted] … they ought to be shot with a double-barreled shotgun … that is my doctrine,” the Latter-day Saint judge thundered. “And when you see these [men] following behind such women … take a double-barreled shotgun and follow them, shoot them to pieces. And if you do not overtake them before they get to their haunts or dens, kill them both.”

Flint later sued Clinton and others for the malicious destruction of her property. On March 15, 1875, 3rd District Judge James McKean ruled in favor of Flint, who received $3,400 for the illegal action.

“The Mormon community was apoplectic with rage,” Stone writes. “Kate Flint reopened her house.”

Formidable madam earns grudging respect

(Via Utah State Historical Society) Dora B. Topham, aka Belle London, who became the “queen of Ogden’s underworld," including Ogden's Electric Alley and the stockade in Salt Lake City.

Stone also recounts the formidable madams whose savvy earned them grudging respect, if not outright acceptance, especially from city leaders who admired their business acumen.

One of them was Dora Della Hughes who arrived in Ogden two decades after the completion of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. In 1890, she married Thomas Topham, a Union Pacific boilerman and barkeeper with a hair-trigger temper.

She eventually left her husband and became Belle London, the “queen of Ogden’s underworld.” According to Stone, the madam looked more like a Victorian era librarian than the head of what was to become a large prostitution syndicate centered on Ogden’s 25th Street.

London bought and operated private parlors, legitimate businesses, bordellos and numerous other real estate assets in the bustling city. She also bought property from a Latter-day Saint businessman and expanded her illicit sex trade by creating Electric Alley, located behind 25th Street.

(University of Utah Marriott Library Special Collections) Ogden's Electric Alley as it appeared in The Salt Lake Tribune in 1908.

Belle’s relationship with Ogden Police Chief Thomas Browning drew the ire of The Tribune, which accused him of protecting and profiting off of the illegal businesses.

“The Ogden chief of police is an active elder in the Mormon church,” The Tribune wrote. “This officer recently dismissed three Catholic policemen … to make way for three Mormons, whom he could better control. Such protection as … Browning gives to Belle London enables her to control absolutely the prostitution of Junction City.”

(Weber State University Stewart Library Special Collections) Thomas E. Browning, Ogden's police chief.

SLC’s stockade — for people, not cattle

London’s success in building her Ogden empire led Salt Lake City Mayor John Bransford and members of the City Council to solicit the madam to invest in and operate a stockade planned for west Salt Lake City. Their goal was to rein in the bordellos that were sprouting up all over the city and confine them to one central walled enclosure where the trade could be easier monitored and controlled.

In 1908, according to Stone, London formed the Citizen’s Investment Co. to buy the land. She served as president, treasurer and general manager of the stockade and controlled nearly all the 2,500 shares. The Salt Lake Security and Trust Co. granted a trust deed for $200,000 and provided the capital required to purchase Block 64 on the city’s west side and to build the stockade.

Enclosed by a 10-foot-high, two-door, gated wall, the stockade was home to 150 small rooms rented to prostitutes for $4 a day. The stockade also featured boardinghouses, a saloon, dance hall, opium dens and restaurants.

(Utah State Historical Society) The stockade brothel, on 200 South, in what was then known as Salt Lake City's red-light district, in 1908.

Alas, the stockade was short-lived. Vigorous opposition from west-siders, along with the public furor stoked by newspapers, tarnished the reputation of public officials who participated in the venture, and London was charged with “pandering,” punishable by 18 years of hard labor.

“Of course,” Stone writes, “after some 22 years in the business of prostitution … (and possibly having a black book filled with [clients’] names), the charges were dropped. The stockade closed for good in 1911. But prostitution in the city survived into the … well, business is business.”

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) History writer Eileen Hallet Stone has a new book out titled "Selling Sex in Utah: A History of Vice,” as she sits for a portrait and talks about the world’s oldest profession and Utah’s more unsavory history on Wednesday, July 12, 2023.

Stone hopes her book will revive this oft-forgotten chapter of Utah’s history and help readers gain a better and more empathetic understanding of how women of that time coped with their unequal status and how that informed the decisions some made to become prostitutes.

“People try to change history to what they can live with,” Stone said. “But this is history that you can’t change or simply wish it wasn’t there. History is something you can learn from, but you can’t change it.”

Editor’s note • This story is available to Salt Lake Tribune subscribers only. Thank you for supporting local journalism.