The Rev. France Davis’ first taste of the Beehive State — a place he had never visited and knew little of — left him reeling.

The Georgia native had marched for voting rights with Martin Luther King Jr. from Selma to Montgomery, had served as an associate pastor, had earned a degree in rhetoric and communication from Berkeley and had accepted a one-year post in the University of Utah’s communication department. But when Davis arrived in Salt Lake City in 1972, the landlord, who had accepted his mailed deposit on an apartment, refused — upon seeing the African American educator — to rent to him.

Not long after that, Davis was invited to speak at Brigham Young University but was escorted off the Provo campus when security officials decided his Afro was not appropriate for the LDS Church-owned school.

Such episodes, and others like it, convinced the earnest young pastor that Utah needed him to stay more than a year and work for change.

Nearly 50 years later, Davis has achieved success beyond all expectations in so many spheres — from civil rights to civic engagement, from educational offerings to social justice, from weekday service to Sunday sermons — especially, and above all, from the pulpit at Salt Lake City’s Calvary Baptist Church, where he has served since 1974.

The passionate preacher, dedicated teacher and acclaimed activist, whose slight stature belies his outsized influence, has been seen as the conscience of the community as he helped fight battles on behalf of Utah’s blacks. He has worked for fair housing laws, educational opportunities and improved health care. He served a decade on the Board of Corrections, which governs how prisons operate and prisoners are treated. He’s given commencement addresses on every one of the state’s public colleges except Utah State University. He was appointed the first black member of the statewide Board of Regents, overseeing higher education, and also has served as chaplain to the U.’s football team. He has written four books about Utah’s black history, including an autobiography. He’s seen the African American community mushroom from 10,000 to 48,000 in Utah, now boasting dozens of predominantly black churches.

“France Davis brings an unparalleled sense of the history of civil rights,” former Gov. Jon Huntsman says. “He’s used his pulpit to lift people and solve problems in ways that state government never could.

“We are fortunate,” he adds, “to have him in our community.”

On Sunday, the 73-year-old Davis will retire after 46 years at Calvary — which he helped build from a small black congregation to a thriving multiethnic community with a lively choir and an empire of social services — which is central to the religious life of the state.

His successor, the Rev. Oscar T. Moses from Chicago, will preach his first sermon Jan. 5.

Davis will stay anchored to this community to which he has given so much, continuing to mentor, reach out, speak up and labor tirelessly to improve the well-being of the African American community, as well as everyone else.

But first, he quips, “I am planning to do a lot of sleeping. After that, the only thing I won’t do is prepare a weekly sermon.”

His wife, Willene Davis, supports his decision to retire.

“If the Lord says it’s time, then it’s time,” she says. “Whatever God has told him to do, I have stood by him.”

The church is his “greatest accomplishment,” Willene says, “but all his work has been positive.”

And it’s all been, she says, “by the grace of God.”

Racial rifts

(Jeremy Harmon | The Salt Lake Tribune) The Rev. France Davis is an important figure in the fight for civil rights in Salt Lake City through his role as pastor of Calvary Baptist Church and his involvement in the local branch of the NAACP.

Davis came to Utah in the early 1970s, when the state’s predominant faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, barred black men and boys from holding the all-male priesthood and black women and girls from entering the faith’s temples.

That church’s racist stance, which ended in 1978, had an impact on many social and political aspects of the state beyond Latter-day Saints.

“If you wanted to go to school, if you wanted to work, if you wanted to be an economic developer, you were negatively affected by that [LDS] belief, which transferred into everyday life,” Davis says on an upcoming episode of The Salt Lake Tribune’s “Mormon Land” podcast. “You could not expect to get the job at the top if you were African or of African descent.”

Davis recalls that when he joined with others to protest the MX missile coming to Utah [in the late 1970s], his office “got shot up, with bullet holes riddling the wall.”

He was not there at the time “or they would have been in my lap,” he says. “I received letters from somebody purporting to belong to the KKK [Ku Klux Klan]. It claimed the Klan was 7,000-strong in Utah and they would pour gasoline on me and burn me alive. I still have that letter.”

Calvary’s mostly black congregation “has endured cross burnings and threats,” he says. “People have been beaten up because of their race.”

The couple’s eldest daughter was told she couldn't walk on the same side of the street as whites, Davis recalls. When she was a student body officer at Skyline High School, she was “not allowed to have music based on her culture during cultural activities. She left for college and didn't want to come back here.”

Over time, though, Davis has been able to open minds and hearts about race, partly by building connections with Latter-day Saint leaders and legislators.

Consider the case of Martin Luther King Day.

When the U.S. government declared that the third Monday in January would be a legal holiday named for the legendary civil rights leader, the Utah Legislature balked, saying the federal law did not apply to this state. When a bill was introduced making it a holiday, it went down resoundingly.

So Davis decided to talk to Latter-day Saint leaders, who agreed not to oppose the bill — and it eventually passed.

Some years ago, Davis had a good-natured exchange with Russell M. Nelson after he attended a concert by the world-renowned Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square.

The Baptist minister told the LDS apostle, now church president, that the Mormon performers were “very good” but “lacking in spirit,” compared with his own Calvary choir.

This year, Nelson described that exchange to delegates at a national NAACP meeting, praising Davis for his “quiet dignity and tireless advocacy for unity [that] have greatly enriched the fabric of our community.”

Blessing the whole community

(Chris Detrick | Tribune file photo) The Rev. France Davis delivers the benediction during the worship service Sunday morning at Calvary Baptist Church, Dec. 31, 2006.

The long-serving pastor has built an “uncommon community” inside and outside Calvary, says Miki Hesleph, who has been a congregant since 1980.

When Hesleph was a member of Calvary’s choir, it would participate with other faith groups beyond Baptists, including Jews, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Catholics and Latter-day Saints. “He makes connections with lots of people,” she says, “and he maintains those connections.”

He also visits smaller Baptist congregations across Utah, Idaho, Wyoming and Nevada.

“My sense of the man is as a hands-on minister of God, which means he is personally involved with everyone, not just those who are his congregants,” says Darius Gray, a Latter-day Saint who served for years as a leader of the Genesis Group for black Mormons and their families. “Whenever he is aware of individuals with financial or legal needs — including many at the Salt Lake County jail — he tends to them quietly and effectively.”

Davis’ style is “understated, thoughtful, purposeful and direct,” Gray says. “Not everyone can do that.”

On one occasion, Gray was walking with the pastor outside the church and told Davis he was in some pain from cancer. The pastor took Gray’s hand right there in the parking lot and offered a prayer of healing.

“He blessed me,” the Latter-day Saint recalls with emotion. “He feels comfortable being an intermediary for God. He’s present in the here and now.”

To “this black Mormon,” Gray says, Davis has made Utah “a better place for all.”

Shepherding a congregation

(Chris Detrick | Tribune file photo) The Rev. France Davis hugs Janelle Douglas, 6, following the worship service Sunday morning at Calvary Baptist Church, Dec. 31, 2006.

In his autobiography, Davis writes that he is “first and foremost a pastor of the church, concerned about the spiritual welfare and well-being of people in our community.”

And the congregation has relished their pastor’s love.

“His strength is his compassion,” says Hesleph, “and his integrity.”

She has seen him “take the coat off his back and give it to somebody who didn’t have one — a student who came from a warm place and wasn’t aware of how cold it can be here.”

Though Davis has come in contact with famous, powerful people, Hesleph says, he doesn’t “carry that as ‘look how fabulous I am.’”

Judge Shauna Graves-Robertson, who has been a Calvary member for 44 years (“He married my husband and me, baptized my children, buried my relatives”), notes the pastor’s advocacy for education.

“There are numerous foundations and scholarships in his name,” says Graves-Robertson, of the Salt Lake County justice court. “He has raised money so that young people would have an opportunity for education. No one can compare to how much he has done in this area.”

At the same time, she emphasizes the bow-tied preacher’s unassuming manner.

After Graves-Robertson had finished college and started her first job, she had to move around a lot. One day, Davis showed up unannounced to lift boxes and carry furniture.

That image has “stuck with me over the years,” Graves-Robertson said. “It’s the kind of person he is.”

Emma Houston, director of diversity for Salt Lake County, has seen Calvary enlarge from a predominantly black church to one that is now multiethnic and multicultural.

Davis has created a “space so welcoming and inclusive for everyone who wants to come and worship with us,” Houston says. “It is the legacy he built and will leave with us.”

His role at Calvary will evolve after his retirement, while he spends his time traveling, writing, teaching, preaching and sometimes filling in for churches that need a pinch-hit pastor.

Going forward, the powerhouse preacher will still pursue justice and goodness for all — much remains to be done — but at a less frenetic pace than he has maintained for decades.

Nature has seasons and so do humans, he says. “This will be a new season of my life.”

Editor’s note • Former Gov. Jon Huntsman is a brother of Salt Lake Tribune Publisher Paul Huntsman.

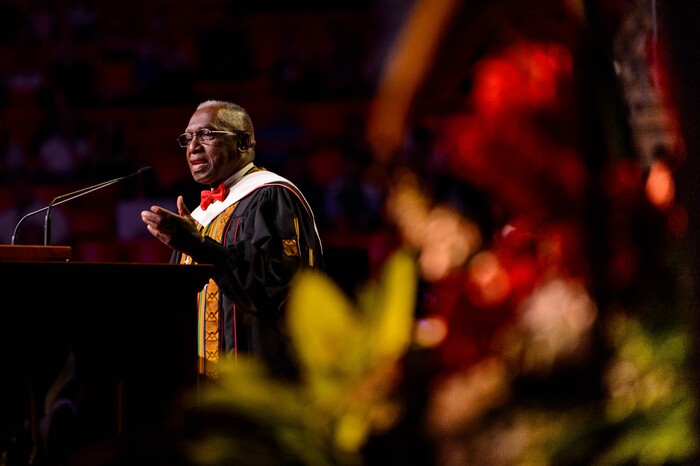

(Rick Egan | The Salt Lake Tribune) The Rev. France Davis preaches his next-to-last sermon at Calvary Baptist Church, Sunday, Dec. 22, 2019.

France Davis in his own words

“Going to public places [in Utah] was sometimes stressful as people stared at [our family] or through us, or made comments about our skin color. In stores we were sometimes followed around as if we were about to take something. In restaurants, we were sometimes ignored. I was determined to do what I could to bring about change.”

“France Davis: An American Story Told”

“One of the stories that my mother [Julia Cooper Davis] told us almost daily was about an activity with her family and the Ku Klux Klan [KKK]. ... Her uncle’s wife was walking and refused to step off, out of the way of some white lady that was walking in the town of Waynesboro [Georgia] and that when she came home that evening, the Ku Klux Klan showed up to get her. Her husband interfered, who was my uncle, and they then took him down to the local African American Baptist church and put him inside, set the church on fire, and he was never seen again.”

“The History Makers: The nation’s largest African American video oral history collection”

“Perhaps the scariest thing that I, as a pastor, must face is the notion that there are hundreds of people who are dependent on me for leadership, for guidance, for direction in terms of their lives. Trust must be earned.”

“France Davis: An American Story Told”

"Be what you is and not what you ain’t, 'cause if you ain’t what you is, then you is what you ain’t.”

His final quote in his 2019 commencement address at the University of Utah.