Republican Rep. Chris Stewart listened Tuesday as leaders of Utah’s refugee community expressed their fears, frustrations and distrust of President Donald Trump.

“One of our biggest concerns,” said longtime advocate Pamela Atkinson, “is we don’t feel the new administration… really understands the refugees and who they are.”

In the first few months of his presidency, Trump has pushed for — and recently succeeded in implementing — a travel ban that blocks for 120 days all refugees seeking to enter the United States (with an exception for those with a “bona fide relationship with a person or entity” already in the country). Stewart briefly defended the policy — as have most of Utah’s congressional delegation — suggesting it is a safeguard against the terrorism that’s plagued Europe in past months.

“If we have one incident of that here, then this whole things becomes very, very difficult,” Stewart said, about the U.S. refugee program. “We don’t have a margin of error.”

Still, the congressman agreed with the leaders that there needs to be a balance in welcoming refugees escaping war-torn regions and protecting U.S. soil. Atkinson, who spoke first at the roundtable before members of the media were ushered out, said she “recognizes” the threat of terrorism, but strongly believes the existing vetting system is more than stringent enough to screen refugees.

With the president’s order, she added, “people approved to come here are sent back to square one.” Stewart nodded his head as she spoke.

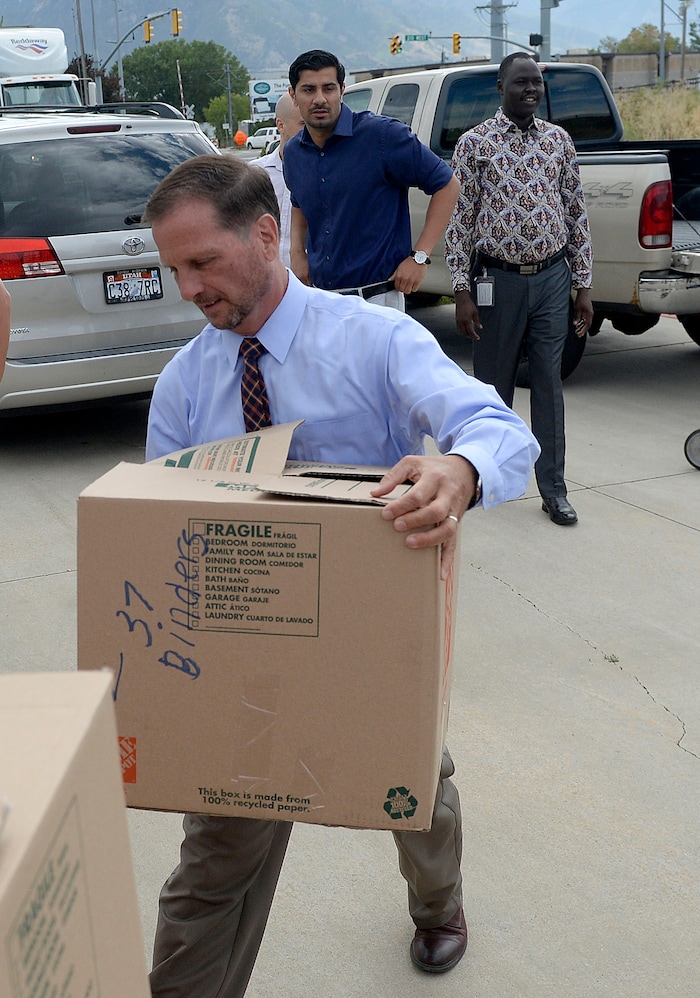

The congressman kicked off the discussion by delivering dozens of boxes of donated school supplies for Utah refugee children. His monthlong drive, in its second year, yielded more than 300 backpacks, 17,000 pencils and 2,000 notebooks to be distributed by the Refugee Services Office.

There are 65,000 resettled refugees living in Utah, said the agency’s director Asha Parekh as Stewart unloaded his pickup truck and carried crayons and erasers inside the Utah Refugee Education and Training Center in South Salt Lake.

(Al Hartmann | The Salt Lake Tribune) Rep. Chris Stewart unloads school supplies from his truck donated by citizens from his district for refugee students at Salt Lake Community College's Medowbrook campus in South Salt Lake Tuesday August 22. He later hosted a roundtable discussion with local refugees.

While Aden Batar appreciates the effort, he can’t help but reflect on the 200 school-age refugee children who were set to come to Utah but were stopped by the president’s executive order.

“We want to see refugees be allowed to come in and no delays be added next year,” said Batar, director of immigration and refugee resettlement for Catholic Community Services of Utah.

Batar and his family moved to Utah from Somalia in 1994 after his 2-year-old son died amid fighting in the country’s civil war. He found his calling here by helping other refugees with housing and schooling.

The discussion Tuesday focused on what work is done locally to help refugees — and how the Trump administration is impinging that, Batar said in an interview after the event. Batar asked Stewart to lobby the president to secure more funding and increase the number of refugees admitted into the United States from 50,000 to 75,000.

Batar was confident the community leaders “showed that refugees are not the problem.”