This story is part of The Salt Lake Tribune’s ongoing commitment to identify solutions to Utah’s biggest challenges through the work of the Innovation Lab. Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Editor’s note • This story is available to Salt Lake Tribune subscribers only. Thank you for supporting local journalism.

Some days, Aileen Hampton has trouble breathing. Hampton, a South Salt Lake resident, has asthma. She can sense when she needs her inhaler within arms reach — during wildfire smoke in the summer, inversion in the winter, or even residual firework fumes after the Fourth of July.

A recent Monday was one of those days, as have been the past couple of weeks. While chatting, Hampton points out heavy breaths between sentences and the hunched posture she’s taken that helps her take in as much oxygen as possible. But the posture isn’t without a cost. It gave her a hernia.

“My lungs are trigger happy — easily set off by the pollutants in the air,” said Hampton.

Asthma rates vary drastically between communities in Utah, disproportionately afflicting areas with high minority populations and low median incomes. Experts say uneven exposure to pollutants and disparities in access to health care are to blame. In Salt Lake City, which faces some of the worst air pollution in the United States, asthma triggers are especially alarming. Asthma is highly treatable but can be fatal if not managed properly, killing over 3,500 people each year in the United States, according to the CDC.

Hampton lives in South Salt Lake, an area with some of the worst asthma emergency room visit rates in the state, according to a 2018 study by the Utah Asthma Program at the University of Utah. South Salt Lake residents are over four times more likely to go to the emergency room with severe asthma symptoms than someone living near the University of Utah just a ten minute drive away.

The Utah Department of Health’s study found the likelihood to seek emergency room care for an asthma attack varies drastically across the state.

The most burdened areas sit at the intersection of many risk factors for asthma. They generally have lower incomes and lower rates of insurance coverage, as well as just being lower in altitude and closer to pollution sources like major highways, setting them up for the worst air quality in the Salt Lake Valley.

In the Salt Lake City area, the most impacted neighborhoods are concentrated on the West and South sides, in lower income neighborhoods like Glendale, Rose Park and West Valley City. Glendale residents face the worst burden: 53 emergency room visits for asthma each year per 10,000 people. That’s six times the rate in Park City, a ski town above the valley known for its concentration of wealth.

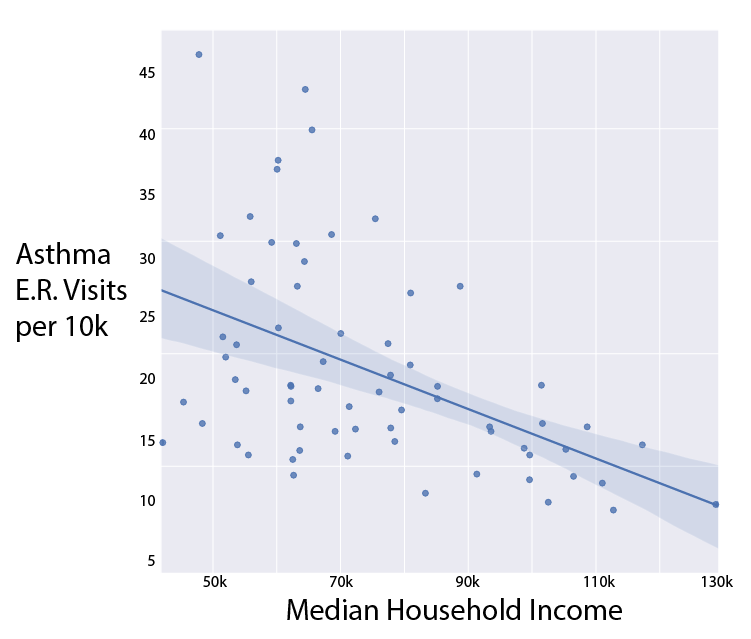

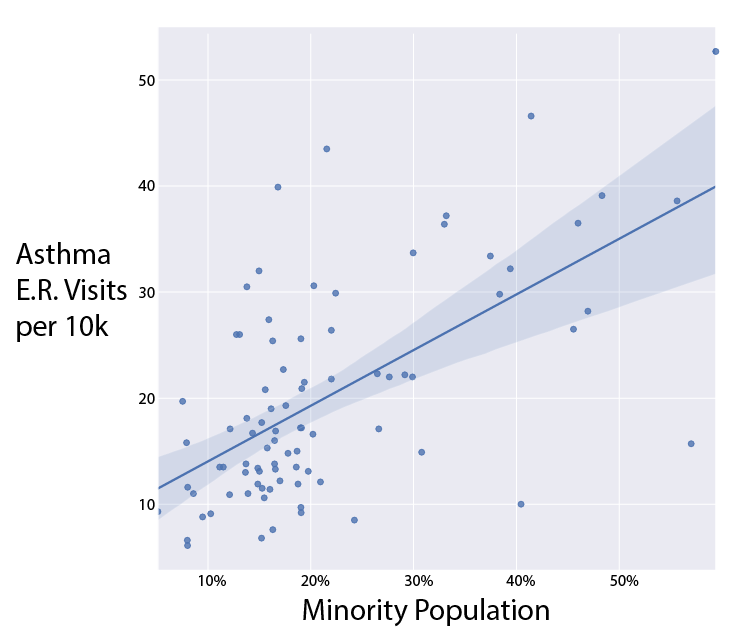

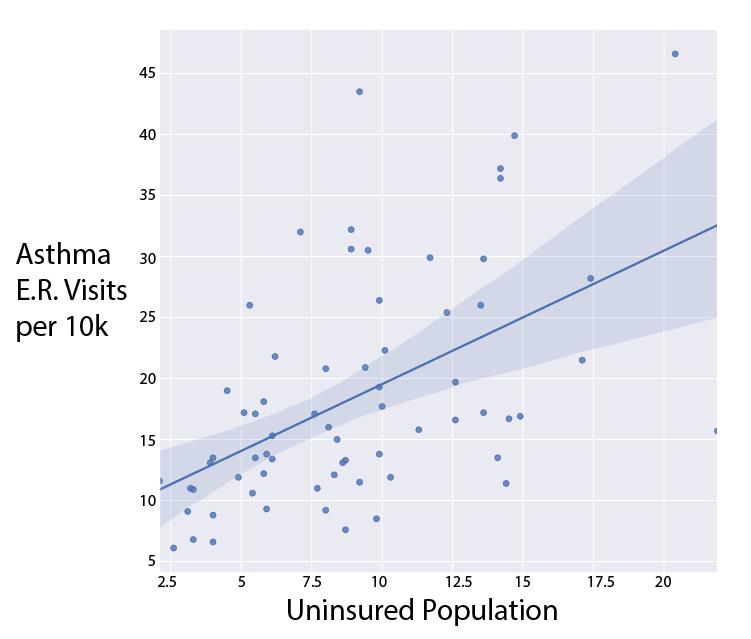

Asthma Burden Compared to Select Demographics

A Salt Lake Tribune analysis of the Utah Department of Health’s most recent Asthma Burden Report combined with Census demographic data found a correlation between asthma emergency room visits and nonwhite populations, health insurance rates and income levels in a given area. Local public health experts cite the same trends.

“This is an issue we see worldwide where minorities and folks of lower socioeconomic status are more severely impacted by the burden of uncontrolled asthma,” said Savannah Smith, Asthma Program Coordinator at the Utah Department of Public Health, “because there are quite a few barriers and risks, like lack of health care.”

Air pollution

For Utahns, asthma starts with bad air.

Seasonally, Salt Lake City can face some of the worst air pollution in the world due to its location between mountains, which can be particularly troubling for asthmatics. Researchers even found that experiencing years of bad air quality reduces life expectancy in the Wasatch Front.

“When I drive in to work, if I can’t see the buildings in Salt Lake City because of air quality, I know I’m going to have a very busy day,” said Dr. Wayne Samuelson, a pulmonologist and professor at the University of Utah who suffers from mild asthma himself.

Automotive pollution is the worst culprit, he said. When people live near highways and freeways, he sees more asthma patients.

The same goes for schools built near major roads, since they are where children spend the majority of their days. Public health experts recommend children with asthma stay inside on days with particularly bad air quality.

The areas with the worst asthma burdens border Salt Lake City’s major interstates. Parts of Glendale and West Salt Lake City with the most dire asthma situations are boxed in completely by highways.

Salt Lake City’s unique geography between mountains further puts these neighborhoods at risk of inhaling dangerous air. In the winter inversion season, pollution gets trapped between the mountains, in what’s commonly called “the bowl.” These areas sit at the bottom of the bowl, where the pollution settles.

Some residents, who live higher up on hills above the city, can escape the smog, even if they have to spend some time downtown during the day. These people are wealthier on average, more likely to be white and have better access to health care, living in areas like the Avenues, Alpine and Park City.

“When you look at neighborhoods and their demographics, you’re going to see the more wealthy living above the inversion,” said Smith. “They’re not living in South Salt Lake, Rose Park, Kearns, Magna and Glendale, where we see the highest rates of emergency department visits.”

The same dynamics play out in the summer, when the combination of gas emissions, ozone and wildfire smoke from nearby states can wreak havoc on the fragile lungs of people with asthma.

Bad air quality does not end outdoors though.

Plenty of indoor risks exist, according to Dr. Denitza Blagev, a pulmonary medicine physician at Intermountain Healthcare.

“Things like exposure to cockroaches, dust or other indoor air pollution is associated with increased risk of developing more severe asthma,” Blagev said. “There’s disproportionate asthma rates in inner cities, associated with the housing quality.” Cheaper housing is riddled with these conditions more often.

To improve things a bit, she recommends frequent vacuuming, refraining from smoking and not using wood-burning fireplaces. Getting an air filter helps too, though they can cost over a hundred dollars and require maintenance.

For people with asthma in Salt Lake and Utah Counties, the Utah Department of Health offers a series of free home visits to gauge risks present in the household and suggest ways to asthma-proof them. They even offer gift cards for groceries as an incentive for some visits. Beyond that, the health department offers remote health visits and asthma education programs, according to Asthma Program Coordinator Savannah Smith.

Health coverage

Though asthma is considered extremely treatable and asthma attacks are often preventable, families scraping by without health insurance coverage can find it impossible to manage. Seeing a doctor and purchasing medications can be prohibitively expensive, leading patients to suffer until the point of emergency.

“The best therapy for an asthma attack is not to have one -- to prevent it,” said Samuelson. “But even the basic inhaler most asthmatics should be carrying around is 60 bucks, which is a lot of money for people struggling to make ends meet every day.”

Hampton, of South Salt Lake, is lucky to have found the right medical assistance to manage her asthma in advance. She takes corticosteroids to keep her airways at ease, with a rescue inhaler for when she does have trouble breathing. In an emergency, she has additional options, too.

“I suffered a lot as a child when my medication wasn’t under control,” said Hampton. “I would wake up and not be able to sleep at night. I’d find something to read and try to distract myself, sitting in a weird position — breathing in, breathing out. I was always certain I would die from it.”

Solutions in practice

Eliminating asthma burden in the Valley will require action on both the individual and policy level, experts say.

Dr. Wayne Samuelson has some recommendations for personal behaviors to combat asthma flares in addition to medication.

“Generally, things you do for good health are good for asthma,” said Dr. Samuelson. “Get good cardiovascular exercise, like a 20 to 30 minute walk. Eat healthy food, don’t smoke and be careful about where you go with regards to air quality.”

As far as policies go, Smith of the Department of Public Health stresses preventive care, which can not only save asthmatics from suffering, but lower costs in the health care system. Smith imagines policies like reimbursement for doctor visits and tele-health care, as well as help on more day-to-day improvements like home weatherization and purchasing air filters to get rid of irritants in the home.

Beyond that, she sees other improvements that can be made: requiring landlords to meet certain guidelines when putting a home on the market, modifying school buses to run more cleanly and even mask wearing on particularly smoggy days.

And as Utah continues to boom and develop new infrastructure, Dr. Denitza Blagev of Intermountain Healthcare hopes for development that keeps this public health issue in mind.

“The inequities are related to where freeways get built and how close to busy arteries of traffic these homes and schools are,” Blagev said. “We have to take into account the impact on those communities as we expand, especially with the influx of growth we have had.”