This article is part of The Salt Lake Tribune’s New to Utah series. For more articles on Utah’s food, culture, history, outdoors and more, sign up for the newsletter at https://www.sltrib.com/new-to-utah/.

From its role in the creation of the internet to its wired population and increasingly tech-influenced economy today, Utah has been shaped by a history with computers that stretches back decades.

Here are five milestones in that history.

University of Utah helped launch the internet

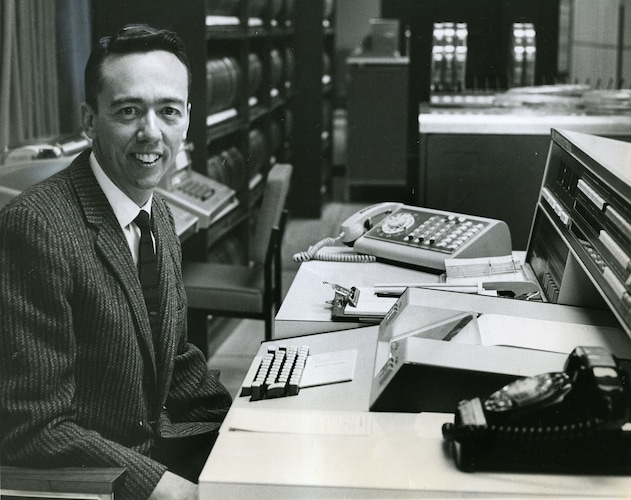

(The Salt Lake Tribune | File photo) Dr. David Evans' hiring in 1966 as the University of Utah's first director of computer science led to the school's role in the birth of the Internet.

Two key factors led to the U.’s role in the creation of the internet: Utah native David C. Evans’ return to campus and the arrival of millions of Department of Defense dollars he brought with him.

Evans had earned his doctorate in physics from the U., worked at Bendix Corp. and then taught at University of California at Berkeley. There, he managed a center funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA, which President Dwight Eisenhower had created in response to the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957.

Then-U. President James C. Fletcher recruited Evans in 1965 to create and lead a computer science department. Evans convinced ARPA to invest in research at the U., and the money bought a large mainframe computer.

When ARPA was ready to try connecting computer projects it had funded, hoping to empower researchers to communicate and share files, some sites balked. But the U. wanted in, and was chosen as one of the first four nodes of what was called ARPANET, the forerunner of today’s internet.

“Utah was the fourth node, and this made what we considered an important step in networking — having four computers up and interworking,” computer networking pioneer Robert Taylor told The Salt Lake Tribune on the 40th anniversary. He left ARPA to briefly join Evans at the U.

“The accomplishment that we felt from adding Utah,” he said, “was that we had the largest network ever put together, established from scratch in one year, 1969.”

[Read more: University of Utah helped give birth to the internet]

The iconic Utah Volkswagen, hand and teapot: breakthroughs in computer graphics

(© Mark Richards. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum) University of Utah doctoral student Martin Newell used a Melitta teapot purchased at a ZCMI department store to create a famous digital version. Martin and his wife Sandra donated the teapot to the Computer History Museum in 1984, and it moved with the museum from Boston to Mountain View, Calif., in the mid-1990s.

The talent and money that combined at the U. in the late 1960s made groundbreaking advances in the creation of three-dimensional computer graphics.

At ARPA, Ivan Sutherland had funded Evans’ work at Berkeley. In 1968, he left a tenured professorship at Harvard to start computer graphics company Evans & Sutherland with him in Salt Lake City.

Sutherland also taught at the U., where Evans had focused the program on one problem: “How do we make realistic-looking pictures? That was the focus and it was a clear focus,” Sutherland said in a 2017 interview published in IEEE Annals of the History of Computing.

Using the era’s improved hardware, researchers were trying to create digital versions of all sorts of objects, including taking on the challenge of producing curves. Sutherland’s students meticulously measured his wife’s 1967 Volkswagen Beetle using flat-surface polygons, and the point coordinates were later used to create a digital version, considered one of the earliest 3D computer models.

In the same period, Ed Catmull — a student who would go on to become a co-founder of Pixar — sketched polygons onto a model of his left hand to animate it in a short film with fellow student Fred Parke.

The film was a landmark, according to Craig Caldwell, a senior research professor in digital media at the U., because “it showed the potential of putting a three-dimensional form in the computer.” It was added to the National Film Registry in 2011.

Graduate student Martin Newell wanted to show the usefulness of another method — using Bézier curves, rather than polygons — and his wife Sandra suggested he use their tea set. He focused on a Melitta teapot they had bought from a ZCMI department store for its combination of properties: It cast a shadow on itself, it was round but didn’t have overly complex curves, and had a concave space created by its handle.

When Newell shared his data set, he gave other graphics researchers a starting point to test their own ideas. A designer who wanted to explore how shading could make an object appear more realistic could just start working on the teapot — without the tedium of first envisioning and creating another effective model.

What followed for the Utah teapot, Newell said, was “the 1970s version of something going viral.”

[Read more: Whatever happened to ... the ubiquitous digital ‘Utah teapot’?]

Teapots have popped up in homage. One is featured in a nightmarish third dimension discovered by Homer Simpson in a Halloween-themed episode of “The Simpsons.” In Pixar’s “Toy Story,” when Hannah sits to tea with an armless Buzz Lightyear, she pours from a Utah teapot.

As the U. celebrated the 50th anniversary of computer science evolving from a division of the College of Engineering to standalone department in 1973, it said these early advances in computer modeling “would ignite a revolution that would lead to computer simulations, medical imaging, computer molecular graphics, computer-animated movies, video games and more.”

Today, the U.’s Division of Games is routinely ranked as among the best programs in the country.

Utah became an early tech business launchpad

(Screengrab) At a March 2023 celebration, the University of Utah displayed these company and movie logos to show the impact of its computer science programs.

Evans & Sutherland grew into a computer graphics powerhouse, and today develops simulations and other visual systems for scientific, commercial and military use.

It’s just one of many influential tech companies launched from the 1960s through the 1980s that trace their lineage to Utah.

Catmull became co-founder of Pixar Animation Studios. The late John Warnock, who developed a key computer graphics algorithm as a doctoral student at the U. and worked at Evans & Sutherland, became a co-founder of Adobe Systems and is credited with inventing the PDF.

Jim Clark, who earned his doctorate at the U., founded Netscape and Silicon Graphics. Nolan Bushnell — the inventor of Pong, founder of Atari and considered the father of electronic gaming — earned his engineering degree at the U., because it wasn’t yet awarding computer science degrees.

One of Evans’ former students, Brigham Young University professor Alan Ashton, joined forces with one of his own former graduate students, Bruce Bastian, to develop a word processing program for the city of Orem. Their software became WordPerfect, which by 1991 had grown into a company with $533 million in sales and more than 4,000 employees.

In the early 1980s, a group of BYU computer science students began working with Novell Data Systems, leading to Novell’s NetWare network operating system that dominated the market into the early 1990s.

“Because of all the energy from local universities, companies, and people, more and more tech companies started in Utah Valley. By the early 1990s, this area was called ‘Software Valley,’” Val Hale, then executive director of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, wrote in 2020.

WordPerfect was sold to Novell in 1994, as both companies were facing intense pressure from Microsoft, and Novell’s dominance faded. “Early successes like WordPerfect and Novell,” Utah Business magazine later wrote, “gave way to a period of simmering, slow development.”

The rise of Silicon Slopes and Utah’s tech economy

(The Salt Lake Tribune) Left: Salt Lake Tribune print coverage in 2008 on the genesis of Silicon Slopes. Right: Attendees walk the concourse of the Delta Center during the Silicon Slopes Summit in 2023.

In what many saw as the start of a new era for tech in Utah, software giant Adobe bought web analytics company Omniture, then based in Orem, for $1.8 billion in 2009. Co-founder Josh James had coined the name “Silicon Slopes” to draw investor and industry interest and talent to Utah.

Adobe opened a new building in Lehi and later expanded its Utah headquarters; Microsoft and eBay also opened offices here as homegrown software-as-a-service and e-commerce companies flourished.

The year 2018 saw successful stock offerings by Utah online tech training company Pluralsight and James’ new business analytics company, Domo — only to be capped that September by the $8 billion acquisition of customer-survey software firm Qualtrics in Provo by SAP, a German multinational powerhouse in cloud and business services.

[Read more: What does the $8 billion deal for Utah’s Qualtrics mean for Silicon Slopes?]

A 2019 analysis found that employment in Utah’s technology sector had grown at twice the national average over the previous 10 years, and the industry supported 1 in every 7 jobs in the state.

By 2021, there were 29 businesses in Utah classified as tech companies that reported having at least 500 employees, according to the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute at the University of Utah.

Utah tech companies with the largest workforces in 2021

In 2022 and 2023, however, layoffs rippled across Utah’s tech sector. Three Utah companies with valuations over $1 billion — MX, plus Route and Podium — were among those shedding employees in 2022. Pluralsight, which was acquired by Vista Equity Partners in 2021 for $3.8 billion, in July saw a third round of recent layoffs.

Qualtrics shed nearly 5% of its global workforce in January 2023 and was sold months later to private equity firm Silver Lake for $12.5 billion. “I couldn’t be more excited for this step in our journey,” Ryan Smith, a co-founder who is now the owner of the Utah Jazz, said of the sale.

Then more layoffs, amid a restructuring that cut about 15% of the workforce, were announced in October 2023.

Utah also has become home to dozens of data centers, including the U.S. National Security Agency’s surveillance operation in Bluffdale and Facebook’s facility in Eagle Mountain, which consume millions of gallons of water a year.

While Utah has been fighting historic drought conditions, Gov. Spencer Cox said in February 2023 that he believes the state has the water infrastructure to support Texas Instruments’ $11 billion plan to expand its semiconductor manufacturing in Lehi, considered the largest private economic investment in the state.

Utah has led the nation in computer ownership

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) Daly Elias uses the space at the WeWork co-working space at The Gateway on Friday, Sept. 2, 2022.

Along with the state’s young population, the state’s rich tech history is often cited as one reason why Utahns began owning computers and gaining internet access at a rate faster than the nation, a pace that continued.

By 2011, one out of every four Utahns were what the Census Bureau calls “highly connected” — people who access the Internet on multiple devices, from computers to smartphones to tablets, from multiple locations. Utah was No. 1 in the nation for internet access, based on that 2011 census data, with just 7.5% of residents age 3 or older lacking the internet at home.

Based on 2013 data, Utah ranked No. 1 in the nation for the percentage of residents who lived in a home with a computer — at 94.9 percent. The national average was 88.4 percent. Five of the nation’s top nine metropolitan areas for computer ownership were in Utah.

Now, 93.6% of Utah households have a broadband internet subscription, which is still above the national percentage, according to recent census data.

For those still lacking high-speed access, the state Utah Broadband Center is developing a plan to distribute $317.4 million in federal funding for broadband projects around the state. And to prepare Utahns and others interested in tech careers, the state’s universities are expanding their programs and raising new buildings.

The need for tech workers “actually becomes a constraint on the growth of companies here,” said Richard Brown, dean of the U.’s College of Engineering, which includes the Kahlert School of Computing. “And we can help. It’s an exciting time to be in engineering and computer science and in Utah.”

Editor’s note • This story includes previous Tribune reporting by Tom Harvey, Matthew Piper, Lee Davidson, Tony Semerad and others. Managing editor Sheila R. McCann contributed to this report.