Reliable as cicadas, grand plans for urban renewal in the heart of Salt Lake City seem to hatch every 10 years or so.

Notions of multimillion-dollar redevelopments over multiple downtown blocks with visions of economic transformation have pulsed each decade at least since the late 1960s, when the overhaul that flattened most of Japantown paved the way for the Salt Palace Convention Center.

Just what light that recurring pattern shines on the city’s latest downtown debate over creating a taxpayer-funded sports, entertainment, culture and convention district on three blocks east of the Delta Center, depends on your perspective.

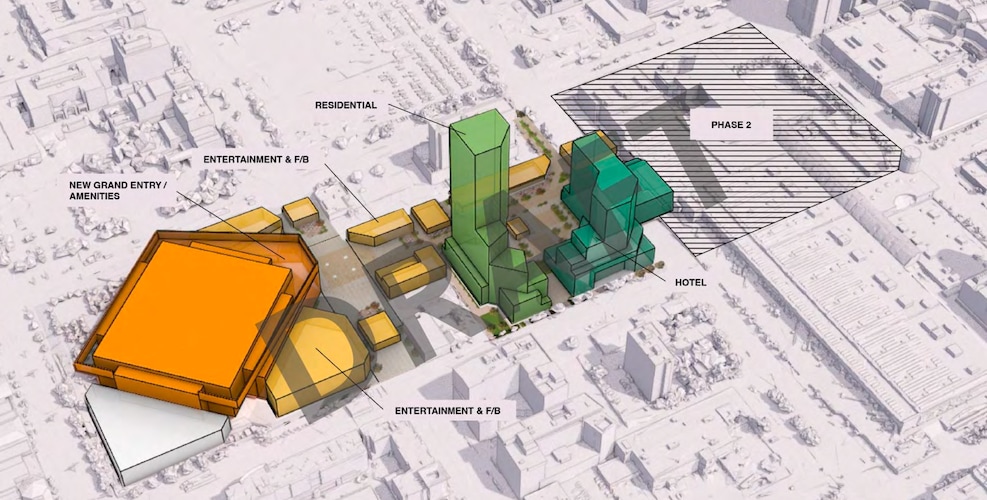

(Smith Entertainment Group) A site plan for a proposed downtown sports and entertainment district.

Key contours of the multibillion-dollar project pursued by Smith Entertainment Group, owners of the Utah Jazz and a new NHL team, have been endorsed by the City Council and are now under review by a state committee, before a council vote on a half-a-percentage-point sales tax hike to pump $900 million into the district.

A Salt Lake Tribune story, published July 21, explored what long-standing challenges such a district could help address in the city’s core, including the prospect of making it more livable, more walkable and greener for a dramatically rising residential population.

The SEG vision also promises urban revitalization, echoing so many past proposals for transforming portions of the city center, dubbed Utah’s living room.

Depending on how you count them, this latest one marks at least the seventh large-scale downtown overhaul to come along since the post-World War II housing boom and an ensuing mid-20th century flight to the suburbs — each driven by its own economic trends and demographics.

In detailing the projected economic impact of the SEG plan, Natalie Gochnour, senior economist with University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, likened the new district to the latest leg in a relay race, with each generation taking its turn at city-building.

Only through consistent commitment to investing in landmark, often public-private development projects downtown, she said, has Utah’s capital fought off urban decay and declines in population that have sapped other metropolitan areas.

“If regions fail to carefully plan, invest, partner and act when the moment is right, the centrifugal pull leaves behind a hollowed-out urban core,” Gochnour wrote in a Tribune op-ed urging support for the SEG proposal. “... The commitment to invest $3 billion of private capital in Utah’s urban center will be a boon to the entire state.”

A countering view surfaced during the city planning commission’s rejection of the sought-after zoning changes. Members said aspects of the SEG plan looked like a familiar pattern of “downtown saviors” whose work later cries out for expensive renovation — and that the tall buildings, large plazas, digital sign concessions and mixed-use developments could all be obsolete within a generation.

“This is no way to plan a city,” said commissioner member Brenda Scheer, professor emeritus of architecture and planning at the U. “The key to urban development is to create a framework for orderly and incremental change by multiple actors, not to demolish entire two or more 10-acre blocks, close streets, and build a single unified vision.

“Anyone who believes that a JumboTron-fueled, oversized and glitzy sports center will be anything but a relic needing overhaul in less than 20 years,” Scheer said, “needs to turn off their VCR and join the real world.”

Here’s a quick look at some of the downtown’s past large-scale redevelopments:

Salt Palace Convention Center

(Utah Symphony) The parking lot at the former Salt Palace is seen in this undated photo. The site would later become the home of Abravanel Hall.

The city’s first downtown convention center was built in the late 1960s amid a mild national recession, with hopes of boosting Utah tourism and drawing new investment. Its construction felled most of Japantown — by then a thriving enclave of Asian immigrant-run businesses, stores, restaurants, homes and cultural spots, which were deemed “urban blight” and taken over through eminent domain.

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) The current Calvin L. Rampton Salt Palace Convention Center.

A few years after the Delta Center was completed in 1991, the original drum-shaped Salt Palace arena — home to the Utah Jazz and Utah Stars basketball teams and the Salt Lake Golden Eagles hockey club — got razed to make way for the expanded Calvin L. Rampton Salt Palace Convention Center, which opened in 1996.

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) The new 700-room Hyatt Regency Salt Lake City Hotel, pictured on Thursday, Aug. 25, 2022, nears completion with a planned opening in mid-October.

To expand capacity for hosting large conventions, the luxury 26-story, 700-room Hyatt Regency Salt Lake City was added atop a southern corner of the convention center in 2022, with two massive ballrooms, a grand lobby with Utah-themed art, three restaurants and a sixth-floor terrace.

Crossroads Plaza and ZCMI Center malls

(Al Hartmann | The Salt Lake Tribune) Street musician Chris Jacoby plays his violin to the noon crowds walking between Crossroads Plaza and the ZCMI Center on Main Street in Salt Lake City in 2004.

Downtown malls came after the Salt Palace in the early 1980s as newly constructed Crossroads Plaza and a pepped-up ZCMI Center along Main Street sought to lure suburban shoppers back to a sagging city center. These sprawling indoor retail centers were the emblem of downtown shopping for a time, but, by the early 2000s, Crossroads and ZCMI were losing customers to suburban malls, and major retail anchors started bailing.

Triad Center

(Chris Samuels | The Salt Lake Tribune) The offices of KSL, Deseret News and other entities of Deseret Management Corp. in Salt Lake City in November 2023.

Oft-forgotten from the 1980s, this development envisioned two game-changing 43-story skyscrapers and three 25-story mid-rise residential towers on three blocks at North Temple and 300 West. Financed by Saudi businessman and arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi and his family, the venture went bankrupt after two phases.

Gallivan Center and the Delta Center

Fireworks above the Gallivan Center announce the beginning of the new year, 1999.

The city’s Redevelopment Agency unveiled new year-round public spaces and a commercial tower at the John W. Gallivan Utah Center on 200 South and Main Street in the early 1990s. Dubbed a “people place,” the 3.65-acre urban plaza’s amphitheater, midblock open spaces and ice rink serve as popular downtown gathering spots.

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) The Delta Center is pictured on Friday, May 10, 2024.

Gallivan opened around the same time as the Delta Center, at 300 West and South Temple. The venue replaced the original Salt Palace’s arena as home to the Utah Jazz.

Some 25 years and major renovations later, the Delta Center again is set for another face-lift, according to SEG, in order to accommodate both the Jazz and SEG’s newly acquired NHL franchise.

The Gateway

(Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune) Thousands watched professional snowboarders throw down tricks on handrails at The Gateway's Olympic Plaza in February 2023 as part of the NBA All-Star Weekend.

As the 2002 Winter Olympics approached, the city drew on taxpayer support to construct The Gateway shopping center at 300 West near the Union Pacific Depot, lauding the pedestrian-oriented open-air mall as downtown’s latest commercial catalyst and a westward nudge for the urban core.

The Gateway, adjacent to the Delta Center, has seen its own struggles since, particularly with retail sales after the opening of City Creek Center a few blocks away in 2012. With store vacancies at all-time lows, The Gateway got acquired by Arizona-based Vestar in 2016 and has since evolved into more of an office and entertainment center.

The property is included in the SEG proposed boundaries for a taxing district to pay for the new entertainment district, but it appears unlikely it will see any taxpayer-funded renovations.

City Creek Center

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune)The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' charity Giving Machines are featured in the plaza at City Creek Center in November 2021.

This upscale addition to downtown by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints opened on Main Street in 2012 — right as the country emerged from the Great Recession. Threaded with a resurfaced version of City Creek, the retail center across from Temple Square replaced the older malls with a $1.5 billion-plus complex covered with a retractable roof and dotted with residential and office towers spread over two blocks.

There’s no doubt City Creek brought an economic lift to downtown’s doldrums at the time it opened, but some critics say elements of the center’s award-winning design — luxury shops, skywalk over Main, inward facing boundaries and behavior rules — tend to give it an elitist and insular feel.

Editor’s note • This story is available to Salt Lake Tribune subscribers only. Thank you for supporting local journalism.