This story is part of The Salt Lake Tribune’s ongoing commitment to identify solutions to Utah’s biggest challenges through the work of the Innovation Lab.

[Subscribe to our newsletter here]

The wheels of the Uinta Basin’s economy are greased again.

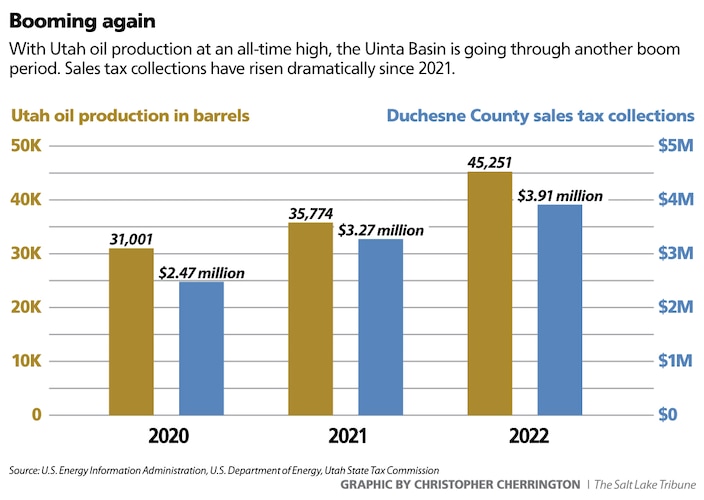

With Utah’s petroleum production rising to record levels, the oil-rich basin in eastern Utah is back in boom times.

Utah employment in the oil and gas industry rose 16% between 2021 and 2022, adding more than a thousand workers to bring the total to 7,449. Most of those jobs are in Duchesne and Uinta counties, where 85% of Utah’s petroleum production takes place.

And those workers are spending. Sales tax collections in Duchesne County have jumped 19% in a year.

“We make no bones about it being our primary industry. Agriculture is our backbone, but oil and gas are our bread and butter,” said Duchesne County Commissioner Irene Hansen.

(Christopher Cherrington | The Salt Lake Tribune)

Thomas Holst, senior energy economist for the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute who previously worked for Exxon Mobil and Chevron, said after dropping down to zero drilling operations during the pandemic, there are now about 15 active drilling projects going on in the state.

And while Utah’s refineries continue to take about 85,000 barrels a day from the basin, the growth is coming from Texas and Louisiana.

“It has to have a buyer,” Holst said. “What is happening is Gulf Coast refineries are developing an appetite for Uinta Basin waxy crude.”

Oil from the basin has a high paraffin content that makes it a solid instead of a liquid at temperatures under 110 degrees. That has made it less valuable in the past because shipping it requires heated containers.

“It can’t be put in a pipeline,” Holst said. “If it moves anywhere, it has to move by a truck that is insulated.”

Hundreds of daily truck trips deliver the crude to refineries north of Salt Lake City and to a rail station in Wellington in Carbon County, where it is loaded onto heated train cars for the trip to the Gulf. The growth in demand is driving plans to build a controversial rail line into the basin.

Demand has increased in part because the high wax content is good for producing lubricants. Plus, it’s low in sulfur, which reduces emissions when it’s burned. Holst noted that the International Maritime Organization recently started requiring international shipping vessels to move to low-sulfur fuels, which has helped drive demand for the waxy crude.

(Rick Bowmer | AP) A tanker truck transports oil through the Uinta Basin south of Duchesne on Thursday, July 13, 2023. The waxy crude generated in the area is in demand on the Gulf Coast, which is helping to boost Duchesne County's economy.

“We’re glad to see that prosperity for our people,” said Hansen, who believes her county is also benefiting from the post-pandemic, work-from-anywhere world. She said remote workers are drawn by outdoor recreation and lower housing costs. “We have teachers who teach in China,” she said.

While sales taxes have taken that huge leap in the last couple of years, Hansen said it hasn’t translated to new stores and restaurants. “We are seeing our Amazon sales going up. If you talk to your big chains, they’re not expanding locations at this point.”

But some businesses are expanding their presence, she said, noting a coffee shop in Roosevelt that is now offering lunch and dinner.

But it’s still a challenge to find workers. “A restaurant can’t make it if it has to pay $20 an hour for employees,” she said.

Holst said the USEER employment figures only include the direct employment by oil and gas companies, which ignores the multiplier effect from other businesses that support the industry, meaning everything from the trucking companies to the restaurants.

The million-dollar question — or perhaps billion-dollar question — is how long it will last. The basin has a long history of boom and bust as oil prices have fluctuated, and now there is a worldwide effort to reduce fossil fuel consumption to discourage climate change.

Hansen is optimistic. “For the next 30 to 50 years, it’s going to a very important part of the mixture.” She said the energy from oil provides safety, and “I don’t think Americans are willing to give that up. ... We see the Uinta Basin as a critical part of national security.”

Holst acknowledges that oil demand will peak, but “my honest answer is I don’t know” when that will happen, he said.

The global demand for oil is expected to peak around 2028, according to the International Energy Agency. The demand won’t end then, but is expected to decline as transportation moves to electricity.

The American Petroleum Institute, a trade organization of oil companies, acknowledges that demand will soften, but it thinks the peak will come later.

And in a sign of just how hard the future is to predict, recent research is showing a climate downside to international shipping’s switch to low-sulfur fuels like those produced from Uinta crude.

The sulfur dioxide produced by the ships when they burn high-sulfur fuels are actually seeding clouds. The cargo freighters with high-sulfur fuels produce “ship trails,” clouds that effectively block some solar radiation from reaching the earth. Some research indicates the reduction in ship trails from the fuel switch has led to hotter summers.