Colorado City, Ariz. • A group of women stood together, stunned, hours after dozens of federal agents swarmed their homes at gunpoint and arrested their religious leader as child welfare officials removed nine girls who federal authorities say Samuel Bateman took as wives.

Two young children toddled around the women that September day, while they talked about the raid and contemplated where child welfare officials had taken the girls.

Among them were two women who federal officials have now accused of kidnapping eight of the nine girls, listed last week as missing from group homes in the suburbs of Phoenix. The girls were later found in Spokane, Wash., and federal authorities accuse three of Bateman’s wives of plotting to take the girls from child welfare custody.

They await formal federal charges, while their faith leader remains behind bars in Pinal County, their group scattered nearly two years after they settled in Colorado City.

Bateman was raised in the small town on the Utah-Arizona border, the traditional home base — along with Hildale, Utah — of the polygamous Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Known collectively as “Short Creek,” the community has historically been closed off.

But Bateman’s arrest is one of the latest signs of how much Short Creek is changing and becoming more open.

Several residents reported him to law enforcement for the last two years, police officials have confirmed, as Bateman led his small new offshoot of the FLDS faith. Federal court documents say some told officers they were concerned that Bateman had taken young girls as his wives — a heightened fear as FLDS leader Warren Jeffs’ conviction for sexually assaulting girls he had married still looms over the religious community.

Those concerns put Bateman on the FBI’s radar, and agents who searched his homes were seeking evidence of underage marriages or sexual relationships between adults and children, according to a copy of the warrant shared with The Salt Lake Tribune. A federal agent later wrote in court papers made public last week that authorities believe Bateman has 20 wives.

Willie Jessop, a former bodyguard for Jeffs who became disillusioned after the leader’s arrest on sexual assault charges, said there are several factors that leave Short Creek residents vulnerable to potential abuse.

The people who live there have deep religious conviction, he said. But the traditionally polygamous community also has a history of secrecy and isolation, which Jessop said contributes to a certain innocence.

“You put all those together,” Jessop said, “and you have a toxic situation.”

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Followers of Samuel Bateman in the immediate aftermath of his arrest in September. The FBI sought evidence of underage marriages or sexual relationships between adults and children.

Bateman hasn’t been charged with sexual abuse, though the 46-year-old man faces child abuse charges from prosecutors who say authorities discovered three young girls inside a locked cargo trailer he was pulling near Flagstaff in late August. He also faces federal charges for allegedly instructing his followers to delete the messaging app Signal from his phone after he was arrested that day.

Bateman’s attorney didn’t respond to a request for comments, and Bateman didn’t respond to an email sent to him in jail.

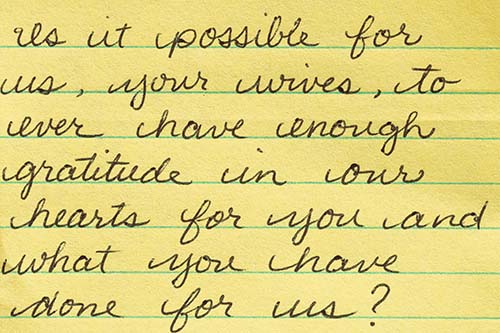

Several of Bateman’s followers who have spoken to The Tribune express deep loyalty and commitment to him. In one display of their devotion, on the day after authorities raided their homes, a group of his closest followers wrote questions on colorful slips of paper that they hoped he would answer on-camera once he was freed from jail.

“Is it possible,” one woman wrote in a neat cursive, “for us, your wives, to ever have enough gratitude in our hearts for you and what you have done for us?”

“How do you know when a Heavenly being is close by your side?” penned another.

“Will we ever have to do without you in this life?” wrote a third.

Explore the series

Growing up in Short Creek

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) The Colorado City, Ariz. home where Samuel Bateman was raised.

Bateman grew up in Short Creek in the 1980s in a Colorado City home in the center of town, close to the Utah-Arizona state line.

He attended public school in the Colorado City Unified School District, according to his LinkedIn profile. It’s the same school district where his father, DeLoy Bateman, taught science — a controversial subject at the time for the fervently religious community.

Lamont Barlow was close with Bateman when they were kids. He remembers Bateman, a cousin on his mother’s side, as an outgoing boy who had a wild streak — once riding his bicycle off a diving board into a swimming pool.

“I did it too,” Barlow said. “I was trying to mimic him. When I did it, I broke my arm. It didn’t work out for me.”

Bateman’s father left the FLDS Church in 1996 and stopped practicing polygamy, asking his “junior wife” to leave, he later told the Denver Post.

DeLoy Bateman had grown frustrated as he saw teenage girls leave school to be married, usually to much older men, and especially after Warren Jeffs moved into a leadership role, he said in the 2001 interview. “When Warren hit, we hardly had any high school girls left.”

In contrast, Barlow recalled his cousin becoming more religious in the 1990s as they reached their late teens, he said, and after Bateman told him he had gone to FLDS church leaders to repent after a romantic relationship.

“At that point, he just dedicated his whole life to the church,” Barlow remembered.

A car crash in 1999 would change Bateman’s life — and many others.

The rollover happened on Jan. 6, 1999, as a group from Short Creek was headed north to Canada to another polygamous community.

Victoria Cooke was 14 years old then. She was riding in the Suburban with her 15-year-old sister, Jami, and four men, including Bateman.

The two young sisters said they were being sent to Winston Blackmore, a polygamous leader in British Columbia. It wasn’t unusual for rebellious kids in Short Creek to stay there, the sisters recalled in a recent interview, with the idea that Blackmore would set them straight. The Cooke sisters had been caught sneaking out to hang out with boys, they said, and were rebellious by FLDS standards.

Jami Cooke had worried, though, that the trip wasn’t just about breaking them of their defiance. She remembers leaving a family meeting with Rulon Jeffs, the FLDS leader in Short Creek at that time, in tears after he implied the young teens were going to Canada to be married.

“These girls would make really good wives for the men up there,” Victoria Cooke quoted Rulon Jeffs, who was succeeded after his death in 2002 by Warren Jeffs, his son.

‘It was like night and day’

The sisters remember feeling uncomfortable getting into that Suburban that January day, because it was unheard of in their community for girls to be with men in a room or in a vehicle without an adult woman with them. But they had little choice, they said.

They remembered Bateman, then in his early 20s, sitting in the front passenger seat, telling jokes and chatting with them during the long drive in an effort to lighten the mood.

“A lot of it centered around how he had been rebellious, but he’d been forgiven,” Jami Cooke remembered. “Once that happened, he had devoted himself to doing what’s right and devoted himself to the Prophet and the Lord.”

(Victoria Cooke) From left, Samuel Bateman, Jami Cooke, and Victoria Cooke are pictured after a 1999 car crash.

As it turned dark, the girls fell asleep draped over one another as they rode through Montana. The next thing Victoria Cooke remembers is waking up to the Suburban rolling. The driver had either fallen asleep or hit black ice — there’ve been conflicting stories over the years, Victoria Cooke said.

The passengers were thrown from the vehicle. Jami Cooke remembers seeing her young sister slumped against a snow-covered hill, her body folded in half like a rag doll.

Bateman was lying on the ground nearby, wailing.

“There is nothing worse than hearing a man gurgle and wail and make the most horrific noises you ever heard in your life,” Victoria Cooke said, her voice breaking with emotion. “[You’re] in the dark, and you’re afraid. And you can’t move. You feel the blood. You can taste the ground.”

They laid injured on the snowy ground for hours until paramedics arrived in the early morning light.

Victoria Cooke and Bateman were the most severely injured, she said, and were taken by medical helicopter to a Missoula hospital. She had broken bones, a punctured lung and a spinal cord injury that would prevent her from ever walking again. He had suffered a significant brain injury, according to family members and others who knew him.

Several people who spoke with The Tribune said this accident changed Bateman. His personality was different, they said, and he was even stricter with his religious beliefs.

“It was like night and day, the person that went in and the person that came out,” Victoria Cooke said. “He was friendly, and then … he was rude, and a bully, and I didn’t even like him around.”

Emerging as a religious leader

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Samuel Bateman leaves the courthouse during the trial of Warren Jeffs in St. George in 2007. Bateman was present as an observer and supporter of Jeffs.

Barlow also remembered seeing this change in his cousin.

“It was almost like a light switch happened,” he said. “He just turned into this very extreme person. He just wasn’t the same guy.”

Bateman started pushing away and shunning anyone who didn’t match his religious fervor, Barlow said.

He had embraced his religion just a few years before their already strict faith was made even stricter, after Warren Jeffs became the FLDS leader in Short Creek in 2002. Jeffs banned most “modern” things, including sports, internet, public education, books, music and television.

But Jeffs soon drew the attention of the FBI, making the agency’s top 10 Most Wanted list after he was charged with having sexual contact with girls he had taken as polygamous wives. He was arrested in 2006.

Bateman was one of about a dozen FLDS followers who attended Jeffs’ trial in St. George on accomplice to rape allegations.

Jeffs’ conviction in that trial was eventually overturned, but he was convicted in 2011 on more serious sexual assault of a child charges in Texas. He is currently serving a life prison sentence.

Eight years after Jeffs’ conviction, Bateman emerged as the leader of a new FLDS splinter group. Members of the group that began following him gave this timeline for how they came together:

In 2019, a group of FLDS people moved from Short Creek to Nebraska for work. Bateman had been struggling financially while working a job selling insurance as his marriage was ending, and he soon followed them out of state, they said.

Warren Jeffs had been in prison for more than a decade by this time, and had remained the group’s prophet despite his incarceration.

But since his arrest in 2006, there had been no new marriages in the community because Jeffs was the only one who could officiate weddings. In late 2010, he told his followers, including married couples, to practice abstinence as part of a cleansing of his church.

Jeffs went silent afterwards. And after nearly a decade, the group in Nebraska decided to pray directly to Heavenly Father, the followers said, and began having children again.

Those who spoke with The Tribune said they felt Bateman seized upon this lack of leadership, telling them that the reason they hadn’t heard from Jeffs was that he was dead or translated — a teaching of the mainstream Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that refers to God changing a person from mortal to immortal.

Jeffs would now only speak through Bateman, who was the new prophet, Bateman told them, and the followers said he started to pressure them to give him money, to bear testimony of him, and for him to be given new wives.

Those who spoke to The Tribune asked not to be identified because of sensitivity surrounding speaking publicly about their religious beliefs.

Bateman soon began to be accepted as a leader.

In a recording of a phone call uploaded to YouTube, a man can be heard saying that the Lord spoke to him and told him to “surrender” his wives and children to Bateman. Saying each of his wives by name, the man declared it so.

“They do belong to Father Samuel,” the man says in the recording.

Vision boards, Bentleys and a white leather jacket

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) The foyer, or "prayer room" of Samuel Bateman's home, with an rendering of a mansion.

Bateman and his followers returned to Short Creek in 2021. Once back in the Utah-Arizona border community with people who believed in him, Bateman seemingly became obsessed with prosperity.

A federal agent wrote in court papers that Bateman didn’t work — and that much of his money came from his own followers.

He posted a series of YouTube videos coaching people on how to realize their ambitions, videos often shot from atop a vista with sweeping views of Colorado City and the surrounding red rocks. In one video, he encouraged viewers to spend money on mentorship programs, saying he has spent about $70,000 on similar efforts.

“The successful people, they do things that unsuccessful people don’t want to do,” he says. “And part of self-discipline is when you have something to do, especially what’s on your goal board or your daily list, do it — even if you don’t feel like it.

Bateman said in his LinkedIn profile he had trained as a pilot and as a scuba diver.

And one of his new dreams included building a sprawling white mansion nestled in the red rocks of southern Utah. A framed rendering was hanging in a gold-accented prayer room in the entrance of his home in September, showing the building with the word “COMING SOON” written in capital letters.

He mentioned in a YouTube video that he had a dream about this new home — a 40-bedroom multimillion dollar marble mansion with an indoor swimming pool where he could bring the queen of England for a visit. He also dreamed of this visit, he said on the video, and had been working to manifest that meeting. (This video was recorded in March, prior to Queen Elizabeth II’s death.)

The spot he’s chosen for his dream home is on federal Bureau of Land Management property, Bateman conceded, but he didn’t care.

“I’m going to put it in my goals,” he said. “I’m going to have this 40-acre piece of property with that house on the corner.”

Those goals were one of several he had written on a whiteboard, according to an image shared with The Tribune. Other goals included: “I own 1 quadrillion in assets for Zion,” “I am the most influential person on Earth for Zion,” and “Made a music album.”

Other vision boards were hanging in a work area of one of his homes, with goals of owning granaries and wheat fields, private jets and a big bus.

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) A dream board at Samuel Bateman's home.

The framed photo includes Bentley cars and Range Rovers — a goal Bateman did accomplish. He was often seen wearing a crisp white leather jacket, traveling on Short Creek’s red dusty dirt roads in a single-file motorcade of two Bentleys sandwiched between two Range Rovers.

And for at least the last year, Bateman had been seen driving around the town pulling a flatbed trailer where more than a dozen girls or young women who he allegedly took his as wives were seated in two neat rows, as seen in a photograph shown to The Tribune.

This flashy lifestyle had started to draw attention from people who lived in Short Creek, a community known in the past for keeping secrets. But this time, the community spoke up — with several people going to law enforcement with concerns regarding Bateman’s relationships with the girls he was parading around town.

Colorado City Chief Marshal Robb Radley confirmed to The Tribune that his office has received several reports about Bateman, but wouldn’t release documents detailing the allegations because its investigation is pending.

He said his department felt it had enough evidence to open a case in June, which he said has since been referred to the FBI.

Three months later, FBI agents descended upon Colorado City on the overcast September morning, the early morning rain turning the red dusty roads to mud as mist clung to the desert cliffs that towered above Short Creek.