Prescriptions from Mexico? Utah is paying public employees to make the trip

Tijuana, Mexico • Hospital Angeles towers over a neighborhood that, but for the palm trees and signs in Spanish, could be in Salt Lake City.

TGI Fridays and Sam’s Club are around the corner. U2 plays on the speakers at a coffee shop across the street. At the end of Paseo de los Héroes, the main street through Tijuana’s medical district, looms a massive statue of Abraham Lincoln.

This is where some Utahns fill their most expensive prescriptions under a cost-saving measure that made national headlines when it was announced. In the first year since the state’s “Rx Tourism” program for public employees launched, 10 Utahns have traveled over the Mexican border to pick up specialty medications at about half the price charged in the United States. In return, the state covers airfares for the patient and a companion, and offers a $500 cash incentive for each trip.

“It was a no-brainer,” said Ann Lovell, who has made four trips to Hospital Angeles in the past year to pick up Enbrel for rheumatoid arthritis. In addition to the cash payment, Lovell avoids the hefty copay she’d have to cover in the U.S. under her plan through PEHP, the insurer that covers 160,000 Utah public employees and family members.

“It’s kind of like $1,000 in my pocket,” Lovell said.

Medical tourism long has been a workaround for Americans seeking procedures that often are not covered by their insurance, and the streets of Tijuana’s medical district are lined with clinics for everything from bariatric surgery to dental care and optometry.

Yet pharma tourism for specialty drugs is a relatively new phenomenon here — and it’s different from the buyer-beware market for medical treatments and procedures.

“At the end of the day,” said Chet Loftis, director of PEHP, “we’re talking about the same drug.”

But the cost is vastly different — typically 40% to 60% of the list price in the United States.

In total, the state has saved $225,000 on drugs bought in Mexico by patients who require any of the dozen or so specialty drugs — mostly treatments for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune disorders — that PEHP identified as having the most potential for savings.

Legislators and PEHP administrators had anticipated more people would participate, said Travis Tolley, clinical operations director for PEHP; Rep. Norm Thurston, R-Provo, said in an interview with National Public Radio last year that he hoped for savings of at least $1 million.

But every client who has made the trip to Tijuana has opted to return, Tolley said, and now PEHP is expanding its travel incentive to Vancouver, Canada, where a clinic is right inside the airport.

In the meantime, state officials have been inundated with requests for information from business and government leaders desperate for solutions to escalating prices for specialty drugs. Though they make up only about 2% of all drugs prescribed, they accounted for about half the money spent on prescription medications in the United States in 2018, according to the health research firm IQVIA.

How it works

The trip to Hospital Angeles is surprisingly quick.

Flying from Salt Lake City to San Diego International Airport takes about two hours. At the base of the baggage claim escalator in San Diego, Javier Ojeda greets first-time patients with a name placard and a driver.

“We never leave [patients'] side,” said Ojeda, general manager of Provide Rx, the pharmacy that works with Hospital Angeles to obtain and dispense specialty drugs for U.S. patients. Provide Rx also makes all travel arrangements, including a motor service staffed by bilingual drivers, who escort patients out of the airport and into a van for the short drive south.

If you blink, you might miss the Mexican border, about 20 minutes from the airport. Southbound travelers aren’t screened, and the van crosses into Tijuana without stopping. It’s another 15 minutes or so to the hospital, via freeways and major thoroughfares.

At 1.6 million people, Tijuana is a sprawling metropolis, but most of the medical services are concentrated in the northern part of the city, not far from the border. Small clinics and large hospital campuses alike stand adjacent to clusters of loft apartment buildings and trendy restaurants in this cosmopolitan neighborhood; there are about a dozen sushi places within a mile of Hospital Angeles.

“Pretty much everyone who’s a little uncomfortable gets here and says, ‘Oh, this is nothing like the def con 5 situation I thought,’” said Joe Willix, chief experience officer for Medical Travel Option. The Texas company matches U.S. employers to international health care providers to reduce the costs of employees' health care.

At the hospital, patients are whisked past manicured tropical plants and through an airy lobby to a doctor’s office. Patients submit medical records to Provide Rx from their U.S. doctors when the trip is booked, but a Mexican physician must meet with each patient and sign off on the prescription for the pharmacy to fill it, Ojeda said.

The doctor’s visit may amount to a quick exchange of papers or a more thorough physical, depending on the patient’s condition. Then Ojeda provides the pre-ordered medication, and the patient is ready to return to San Diego.

From the jetway in Salt Lake City to the exit of Hospital Angeles, getting a prescription can take as little as three or four hours.

Nearly all of the PEHP clients who have visited Tijuana reacted most strongly to the same thing, Tolley said: “The ease of the trip.”

Getting back to San Diego can be a bit trickier. U.S. border officials have created a “medical lane” at the San Ysidro crossing to streamline reentry, and Provide Rx briefs patients on the usual script: “Always declare your medicine as personal use.”

Ojeda said the wait at the border rarely exceeds 90 minutes and usually is much shorter. The Salt Lake Tribune contacted eight PEHP clients who have made the trip, and they reported wait times from 10 to 90 minutes.

But San Ysidro is still the busiest border crossing in the Western Hemisphere, funneling about 90,000 travelers into the United States each day. Patients' flights back to Salt Lake City tend to be scheduled late in the day, Lovell said, to provide a cushion of time in case of border delays.

“It’s a long, long day,” said Lovell, 62, who works as a teacher for deaf students. During a trip in February, for example, she left her home at 5:30 a.m. and didn’t return until midnight, she said.

But the savings of that long day are profound: Enbrel’s list price in the U.S. is nearly $1,300 per weekly dose of 50 mg, and Provide Rx charges less than half that. For 12 weeks of medication, the savings are more than $9,000.

Over a year, the savings for one patient on Enbrel is more than $40,000 — which more than covers four inexpensive plane tickets and the $2,000 in cash incentives.

The question of safety

When Lovell told friends she was planning to take PEHP up on its offer to send her to buy medication in Tijuana, she said, “people thought I was crazy, because Mexico has a bad rap.”

Confirming the safety of the drugs and the trip was the first order of business when PEHP began to create the travel program, Loftis said.

Although Tijuana is now a fast-growing urban center that attracts crowds of international travelers each day, its reputation still suffers from Americans' memories of horrific violence that decimated the tourism industry there about a decade ago, when cartel warfare over trade networks into the U.S. spilled into even the city’s wealthiest areas.

Today, Tijuana’s crime rate is rising precipitously, but it is overwhelmingly focused on local meth users, the Los Angeles Times has reported. That violence is generally invisible to the upscale business districts between the border crossing and Zona Río, the neighborhood where Hospital Angeles stands. All eight PEHP clients contacted by The Tribune said they felt safe during their excursions.

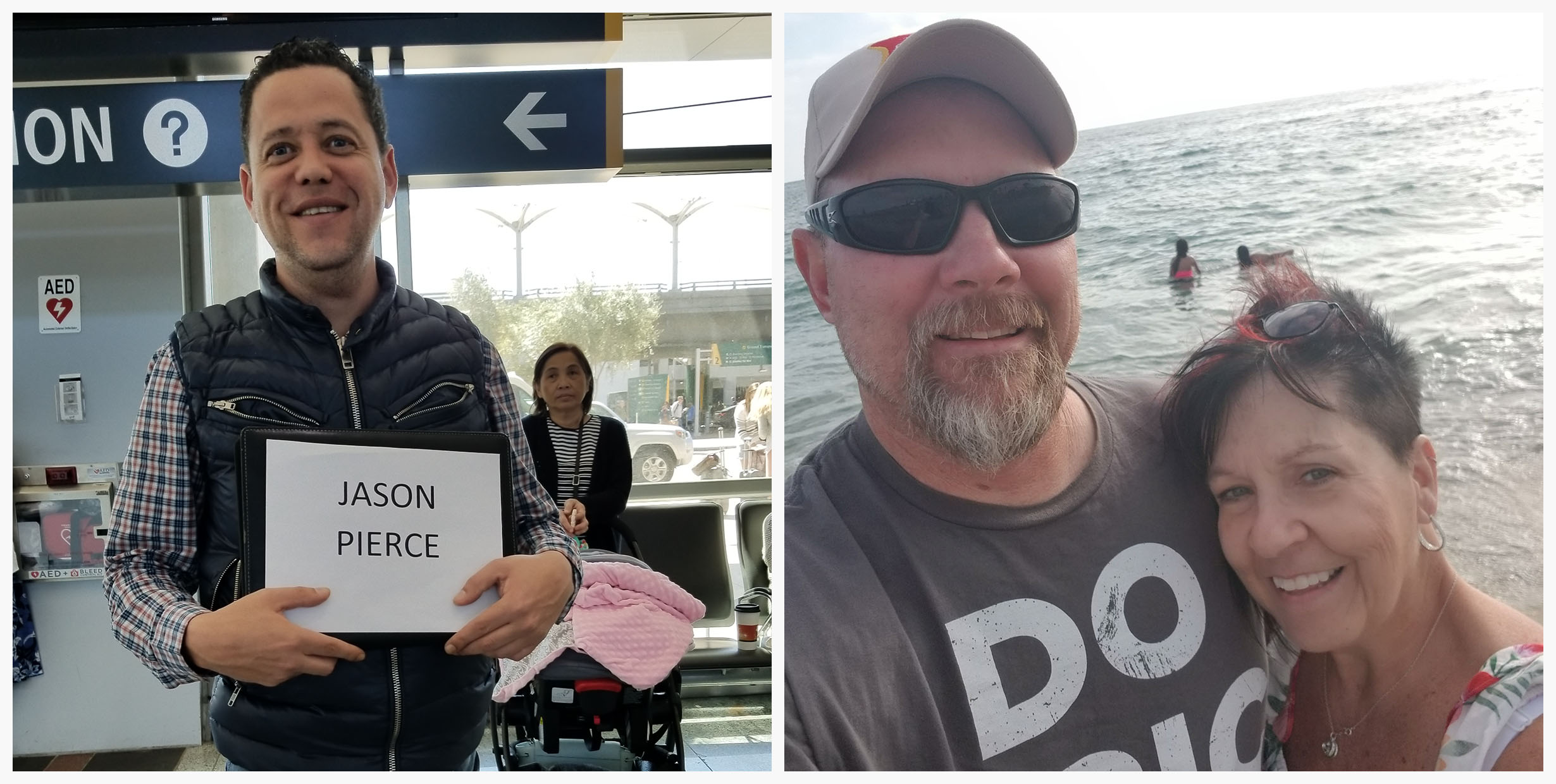

“I was probably the first time a little bit hesitant,” said Jason Pierce, who has made three trips to pick up Stelara — an immunosuppressant that is the most expensive drug on PEHP’s list, at more than $11,700 for a 30-day supply.

“But everything’s been fine. The way they’ve got it set up, they pick you up, they’ve got your name on the piece of paper — you don’t have to worry.”

Lovell, who is deaf, said she initially worried about how she would communicate if something were to go wrong. She has cochlear implants and lip-reads — but accents can make speech difficult for her to understand. And American Sign Language and Mexican Sign Language are mutually unintelligible.

But Ojeda has accompanied her through each visit, she said, and now she feels more confident. “It’s pretty old hat,” Lovell said, “and nothing changes from visit to visit.”

Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cautions that bringing prescription drugs into the United States from another country is illegal “in most circumstances,” Americans are generally allowed to bring 90-day supplies of medications for personal use.

U.S. regulators also warn that medications from outside of the country “do not have the same assurance of safety, effectiveness and quality as drugs subject to FDA oversight.” The World Health Organization in 2017 reported that about one in 10 medical products bought in low- and middle-income countries was either “substandard or falsified.”

But PEHP officials say the drugs bought by Utah patients are strictly regulated. Provide Rx is a boutique pharmacy for high-end medications, and Hospital Angeles — part of the biggest hospital system in Latin America — offers services that compare to major research hospitals in the U.S.

“They’re not stopping at a corner pharmacy across the border,” Tolley said.

To confirm the authenticity of the drugs, Tolley said, PEHP officials tracked the supply chain from the manufacturers to Provide Rx, reviewing lot numbers and verifying the pharmacy’s relationships with wholesalers and manufacturers.

They also looked into safeguards that the Mexican government puts on pharmacies and supply chains, Tolley said. “The rules between the two countries are different but similar.”

In fact, said Becky Winslow, a clinical pharmacy specialist in Delaware, Mexican pharmacy regulations exceed the FDA’s on some points. Winslow, in 2017, was contracted to inspect Provide Rx for a U.S. insurer. Now Winslow works with Apollo Vanguard, a Texas-based health care cost consultant that coordinates trips to Tijuana for the employees of clients.

“I was impressed with their operations,” Winslow said, noting that Provide Rx’s practices complied with U.S. and Mexican standards.

The pharmacy itself is a nondescript office near Hospital Angeles. There is no storefront, because all of its medications are dispensed at the hospital. In fact, the storage room often contains just one box of medication. With 63 U.S. clients filling 138 specialty prescriptions in a little less than two years of operation, Provide Rx typically has each patient’s order delivered individually from one of two wholesalers shortly before they arrive.

Those wholesalers obtain the drugs from the same manufacturers that supply U.S. patients, Ojeda said. All of the Utah patients contacted by The Tribune said their medications performed no differently from those bought in the United States.

“It’s the exact same branding and everything — it’s just in Spanish,” said Lovell. “That took away my fear completely.”

The drugs arrive ready to dispense to the patient; although Provide Rx has a pharmacist on staff, he doesn’t measure out or mix medications. Instead, the pharmacist is focused on ensuring compliance with the detailed requirements of Mexico’s equivalent of the FDA, known as the Federal Committee for Protection from Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS).

Those are the regulations any reputable modern pharmacy in Mexico should be following, said Paulo Yberri, CEO of Hospital Angeles.

Patients who wish to travel on their own to Mexico to buy medication should look for authentic drugs from reliable supply chains, Yberri said.

“Buy straight from the pharmacy. Make sure it’s a well-established pharmacy, that you can see all the appropriate permits, that it’s a formal business place,” Yberri said. “I wouldn’t be pulled into a dark basement to get medications. But if you’re going to a well-established business, it’s regulated.”

Getting employees to go

Before PEHP began offering the $500 cash payout to pick up medication in Tijuana, patients weren’t making the trip.

PEHP for years offered to cover travel to Hospital Angeles for medical procedures after Salt Lake City requested the provision for is employees — but with no other incentive, no one had taken the option, Loftis said. For PEHP clients, the savings from less-expensive prescriptions or care in Mexico mostly benefit the state — and, by extension, taxpayers.

Some employers outside Utah also offer cash incentives to their employees to travel to Mexico for specialty drugs, said Armando Polanco, CEO of Apollo Vanguard. In fact, incentives can be as high as $3,000, he said, though the larger payments are used in part to cover travel and other trip expenses.

Other employers offer paid time off instead, Polanco said. “It’s almost like a little vacation to get away to San Diego.”

That’s what keeps Pierce returning. He and his wife, who is covered by PEHP through her job at the state health department, have extended their trips into regular weekend getaways in Southern California.

Pierce and his wife, Robbin Williams, enjoy a day at the beach during a trip to the U.S.-Mexico border to purchase his refill of Stelara. The prescription drug can be bought in Mexico at less than half the U.S. price. Pierce and Williams have opted to turn their trips into minivacations in Southern California.

“We turn it into a three- or four-day trip,” said Jason Pierce, who is 49. “We just get a hotel or Airbnb, go stay on the beach, hang out and come home.”

Some employers have had success appealing to employees' sense of duty to their coworkers, said Curry Willix, founder of Medical Travel Option. If one person’s major health expense can be reduced, the reasoning goes, it can keep premiums lower for everyone, especially at a small business.

“They do a really good job of educating their employee population about the financial burden they’re under as an employer to provide health care,” Willix said. “They’re doing all they can to not raise employee costs annually, whether it be premiums, deductibles or out-of-pocket expenses.”

One of Willix’s clients has persuaded nearly every eligible employee and dependent to travel to Tijuana to buy specialty drugs.

“Once they understand the process and the benefit to themselves,” Willix said, “pretty much everybody bought in because they do like helping the company.”

But the very existence of a pharma tourism market is a sign of a broken health care system, Willix noted. She’s not surprised, she said, that she has seen only employers with self-insured plans, or a public entity like PEHP, seeking international sources for specialty drugs.

Commercial insurance companies are more enmeshed in a drug supply chain where there is little price transparency, she said.

“The wealth to be gained at the insurance level is significant,” Willix said. “I’m not seeing evidence that they’re really interested in many new ways to do things, like go out of the country to procure services at another price point.”

The American difference

A study released by Congress this year found Americans “pay on average nearly four times more for drugs than other countries — in some cases, 67 times more for the same drug.”

In the 11 other wealthy countries the researchers studied, as well as in Mexico, governments negotiate with drug companies to rein in prices.

The key difference in the United States: Those negotiations are conducted by for-profit companies called pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. Here’s how it works:

Insurance companies hire PBMs to determine which drugs are covered by their health plans and the amount that their patients will pay for them at a pharmacy.

Three PBMs control about 80% of the U.S. drug market, so they are able to demand rebates from pharmaceutical companies in exchange for getting the companies' drugs covered by insurance plans.

PBMs say they pass on those rebates to insurance companies, which can then lower premiums for patients.

Critics say that this system promotes higher prices: Drugmakers have an incentive to raise their list prices so they can compete by offering bigger percentage rebates. And the rebates are generally kept secret — so patients can’t know how much of the rebate PBMs and insurers may be keeping for themselves, or how much a drug would cost if the rebates weren’t built into the prices.

Democrats in the U.S. House in December passed legislation that would allow the federal Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate Medicare prices on 250 commonly used drugs — and would require drugmakers to offer those same prices to private insurers.

But President Donald Trump has said he would veto the bill, arguing it is too restrictive to drugmakers and will suppress research and development. Meanwhile, a bipartisan bill on Medicare drug costs is pending in the U.S. Senate — but it does not authorize the government to negotiate prices.

As the cost disparities persist, some state and federal officials have begun to explore importing drugs from Canada — as federal law has allowed for years. The provision requires the approval of federal regulators, which no state had sought until Vermont began preparing an application in 2018.

Utah legislators last year considered creating a drug import program. But after representatives from the pharmaceutical industry warned it would likely be challenged by federal health officials, state senators defeated the measure in a committee.

Since then, three other states have begun applications, and the Trump administration has said it is open to proposals. Federal administrators in December published draft rules that would allow pharmacies and wholesalers to co-sponsor proposals with government entities to import certain drugs from Canada.

But the rules would exclude many drugs that contribute heavily to U.S. drug spending, such as insulin and several of the drugs in PEHP’s travel option, like Humira and Enbrel.

Meanwhile, the proposal has gotten intense pushback in Canada, where health professionals have said U.S. imports could drain Canada’s supply. Pharmacies in Canada “are not equipped to support the needs of a country 10 times its size without creating important access or quality issues,” the representatives of 15 Canadian health advocacy organizations wrote in July.

Mexican providers have shown no such reluctance to take on U.S. pharmaceutical customers. But physician Noemí Cabrales, who consults with PEHP clients at Hospital Angeles, said that as escalating drug costs drive more and more Americans across the border, care providers in Tijuana have watched with concern — not for the Mexican supply, but for the U.S. patients who are facing a crisis of access to health care.

“In a country like the one you have, as rich as it is, it’s inconceivable,” Cabrales said. “Looking at the problem as a human being and as a professional in medicine, I feel worried. Yeah, some people can come over here. What about the rest?”

The Salt Lake Tribune is reporting on prescription drug prices in Utah through the Association of Health Care Journalists' Fellowship on Health Care Performance, supported by The Commonwealth Fund.