This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

East Carbon, Carbon County • The proposed solution for this small city's budget troubles, as well as the financial bind facing the landfill business that provides much city revenue, is a big problem for some local residents.

So while city leaders back ECDC Environmental's effort to put waste contaminated with toxic PCBs in its massive landfill, a cadre of locals has mounted a campaign to stop it.

"I want 30 years of my life left, not 10," says Janice Hunt, a coal mine worker who was recently laid off. "I want to see my grandkids grow up."

"Our way of life is going to be gone," adds Kent Pilling, a retired miner whose family ranch is tucked into a canyon just below the landfill's southern border. "The natural resources are gone; they're all mined out. Our water, our air — that's all that's left, and now they're goin' to take that."

Although the opponents have protested loudly ever since they learned about the plan late last year, the plan looks almost certain to go forward.

Regulators at the Utah Division of Solid and Hazardous Waste and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have been reviewing ECDC's request to build a new section of its 3,078-acre landfill for PCBs, an industrial chemical that was widely used before its manufacture was banned in 1979. And they hope to finalize a permit change in a few weeks that will allow ECDC to begin going after hundreds of lucrative PCB contracts nationwide.

John Brink, who manages EPA's regional pollution prevention and toxics unit, says his office is scrutinizing the plan to make sure the PCBs stay in the landfill and don't drift into town in the water, soil or airborne dust. Although they are not, in strict regulatory jargon, a "hazardous waste," they certainly can be dangerous, says Brink.

"The building up of PCBs in our bodies is not good for us," he notes, pointing to EPA's determination that it can cause many adverse health impacts. "And that's why EPA regulates them the way we do."

PCBs are regulated under law for dangerous substances, the federal Toxic Substances Control Act, along with harmful substances like asbestos and lead-based paints.

When officials have insisted in public meetings that PCBs are not hazardous, Brink says, "I don't think [officials] are trying to tell anybody this is something to be casual about."

Roy Van Os is poring over the dozens of public comments on ECDC's plans at the state's solid and hazardous waste office.

He notes that polychlorinated biphenyls are ubiquitous in modern life, that people are exposed to them — without harm — every day. After examining the studies, he's concluded, "It's a risk, but it's a such a low risk."

The draft permit he's written for the project would require ECDC to keep roads PCB-free by washing the trucks that carry it, to cover trucks and trains filled with contaminated waste and to bury the waste under clean fill every day. Water monitoring would be stepped up, and new air monitoring would be established to make sure tainted dust doesn't blow into residential areas about a mile away.

"There are some things we do in life that expose us to risk," he says. "Some of those we accept. Some of those we don't."

City Councilman David Maggi said he led opposition to the landfill when it was proposed 20 years ago, but he came to see the value in it, especially with the good-paying jobs it offers and the annual revenues from tipping fees that were estimated to be about $5 million annually by about this time.

A lifelong East Carbon resident, he even worked there for a time after working in the nearby mines for 30 years. And now he sees no problem with the PCB proposal, given that he's been around PCBs — which were widely used for a half-century as coolants, insulating fluids, lubricants and coatings like paint.

"Do I fear PCBs? No," he says. "Am I afraid of regulated garbage? No."

Orlando LaFontaine, a New York transplant and East Carbon mayor, says he understands the wariness about the PCBs — he's the father of four young children — but he's also got the community's economic well-being to consider. Too many people in his town of 1,700 are already beaten down by the bad economy and can't afford to bear any new expenses.

"We're concerned, of course," he says. "But the cards are being dealt to us by the state and the federal government."

He points out that state regulations allow low-concentration PCBs to be buried in ordinary landfills, and that an independent review contracted by the city put the risk at 1/1,000th the level considered harmful by the EPA. And as long as ECDC handles the waste properly, the city isn't in a position to object.

"It's not up to us," he says. "There's no vote I can make."

Besides, he continues, ever since the state Legislature approved a landfill in Tooele a few years ago, shipments to ECDC have plummeted and left city coffers starved. It has meant shortfalls approaching $750,000 in an annual budget of just over $1 million.

City leaders already are reworking the ECDC contract and adding a surcharge on PCBs to pump more tipping fees into the city budget.

At the landfill, Kirk Treece is proud of his company's plan for handling PCBs, while protecting the community from harm.

"Our design package is above and beyond what is required," said Treece, who now oversees the new Tooele landfill, which, like ECDC, is owned by Arizona-based Republic Services, Inc.

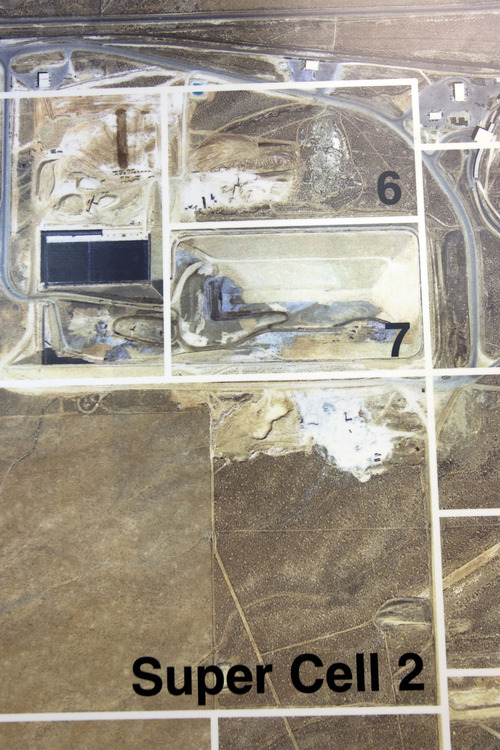

ECDC plans a disposal cell of about 65 acres, lined with super-strong plastic, served by a separate road and updated to ensure contaminated waste stays put. He estimates the cost of these improvements at more than $4.5 million.

A new license will mean the site can compete for PCB disposal contracts nationwide, including the billion-dollar dredging of General Electric plant waste from New York's Hudson River.

"We have a right to do that" says Treece, "to develop the permit."

ECDC was created more than two decades ago to handle trainloads of waste from all over the nation, including the Wasatch Front. But a rail rate hike, the construction of the Tooele landfill and loss of Wasatch Front garbage contracts in recent years are among the changes that have cut deeply into ECDC's business — and revenue going to the city.

The site used to receive 4,000 or 5,000 tons of trash a day. Now it gets about 1,500 tons. PCB disposal will mean new revenue for a site that won't fill up for more than 2,000 years at current disposal rates.

Warren has led the critics, calling on LaFontaine to resign and on Maggio to recuse himself from ECDC votes to avoid a conflict of interest. At a raucous city council meeting last month, Warren accused city leaders of putting residents in harm's way.

The following night, he says, he returned home to find the tires on his truck slashed and a skull and crossbones painted on the back door of this house. Hunt says she has become afraid to speak out — a problem she says many local residents have with other critics of the city's current leadership.

With all Warren has read about the risks of PCBs, he worries about its potential impact on the community. "It's a nightmare down here, I'm telling you," he says.

Meanwhile, Pilling is skeptical that ECDC operations are as safe as they've always insisted. And he wonders how safe are the springs that he relies on for his stock and washwater. (He hauls in bottled water for drinking.)

"It's no-win," he concludes. "I think the decision's made."

Says Hunt, "I hate to feel like we're banging our heads against the wall."

"But that's how it is," says Warren.

Twitter: @judyfutah —

What are PCBs?

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are human-made organic chemicals that were manufactured for a half-century until they were banned in 1979. Because they are non-flammable, chemically stable, have a high boiling point and provide good electrical insulation, PCBs were used widely in electrical, heat transfer, and hydraulic equipment; as plasticizers in paints, plastics, and rubber products; in pigments, dyes, and carbonless copy paper; and many other industrial applications.

People exposed to high concentrations of PCBs and their more hazardous forms, as in fish fat, can experience adverse health effects. PCBs are a probable human carcinogen and have serious non-cancer health impacts in animals, affecting the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and endocrine system.

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency