This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

June 8, 1978, was a sacred, momentous event — a revelation — in the history of Mormonism, catapulting the Utah-based faith into a new era of global growth.

On that day, the LDS Church ended its ban on blacks in its priesthood, opening ordination to "all worthy male members," including those of African descent.

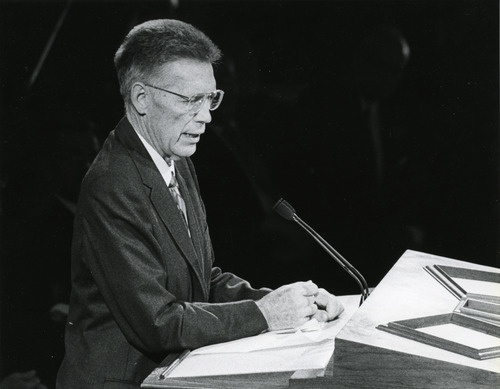

"For me," former church President Gordon B. Hinckley said on the day's 10th anniversary, "it felt as if a conduit opened between the heavenly throne and the kneeling, pleading prophet of God who was joined by his brethren."

In the 35 years since the announcement, Mormonism has spread exponentially in areas formerly off-limits, especially Africa.

There now are nearly 400,000 church members in Africa, thousands of LDS congregational and regional leaders — including several general authorities — with two missionary training centers, three working temples (South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria), with two more planned (Democratic Republic of the Congo and another in South Africa).

Brazil, with its heritage of mixed races, has been especially fertile territory. Witness the more than 1.2 million members. In Europe, many of those willing to listen to Mormon missionaries are African immigrants. And the church is growing steadily in America's inner cities, home to millions of African-Americans.

For most white Mormons, the historical controversy is over.

"It's behind us," Hinckley told "60 Minutes" in 1995.

But the ban still haunts many African-American members. They frequently have to explain themselves and their beliefs to non-Mormons, other black converts, even themselves.

They occasionally hear racist comments from fellow believers, such as "black skin is cursed" or "when you become more righteous, your skin will grow lighter." Some report being called the "N-word."

Such racist remarks exist in every faith and group, of course, but some Latter-day Saints see the persistence as troubling.

"Thirty-five years after the end of a racial restriction that had so burdened the church," says Armand Mauss, a pre-eminent Mormon sociologist, "the old racist folklore that came with it has still not been formally repudiated by the [LDS Church's governing] First Presidency."

Still, Mauss, author of All Abraham's Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage, points to the number of African and African-American LDS leaders "as progress in living it down."

It is that "increase," Mauss says, "that we can and should celebrate most of all on this anniversary."

Dalyn Montgomery, who has studied race relations in higher education, believes he knows what to credit for the progress: Mormonism's structure.

"In both my studies and my experience," says Montgomery, a white Latter-day Saint married to a black convert in Philadelphia, "the LDS Church is structured better than any institution to overcome racial obstacles."

Mixing it up • Throughout U.S. history, the most segregated day of the week has been Sunday. Worshippers often divide along racial lines, attending churches with people who look like themselves.

Mormonism doesn't allow that, Montgomery says. "Because of its lay ministry, everybody has to work together to make Sundays run. In any geography that captures both [black and white] races, people are enabled to spend time together on leadership councils and in each other's homes."

In places such as Philadelphia and Atlanta, he says, a young, white, highly educated family and an older African-American woman of little means "are in each other's homes, meeting in meaningful ways on something — faith — that matters to both of them."

When you add foundational LDS doctrines such as the belief that all humans "are literally children of God, not just figurative brothers and sisters," Montgomery says, "that gives us something tangible to hold on to in crossing that racial divide."

Donte Holland, a black convert of 10 years who is in the bishopric of Philadelphia's LDS Logan Ward (congregation), has put his faith to music. (Listen to two of his songs on the left-hand side of this story.)

"I grew up listening to hip-hop music and didn't want to give up that art form after joining the church," Holland says. "It's a great vehicle to reach people who wouldn't give the gospel a chance otherwise."

But what about regions like Utah with so few blacks?

Mormonism's flagship school, Brigham Young University, has 30,000 students and 1,226 professors, but only 254 black students and one full-time black faculty member, with three black adjunct professors and three other blacks "with faculty status," according to spokesman Todd Hollingshead.

Three multicultural programs meant to prepare black students and others for life on the Provo campus "are currently being reviewed and refocused," Hollingshead said in a statement. The school does offer a program called SOAR for multicultural high school students and a multicultural new-student orientation.

Some argue it would be helpful for all faculty and students to take diversity training.

For Josy Petit, a black BYU graduate from Queens, N.Y., who has been a Mormon since she was 8, being on the largely white campus helped her develop "a sense of humor — and ready answers" when confronted with insensitive comments and false assumptions.

"Even though they knew I was a top performing student, some of my professors just saw a black person," she recalls. "Some of the nicer teachers asked me, 'What sports do you play?' "

Outside of church meetings, "no one acknowledged my existence," she says. "At the year-end closing social, no one talked to me except my roommates. But everyone wanted a picture with me."

Her LDS Spanish-speaking mission to Tampa, Fla., was "wonderful," Petit says, but when she returned to campus, it was not much better.

She got engaged to a white, returned missionary but had to call it off, she says, "because his [LDS] family couldn't get over the fact that I was black."

Petit believes such prejudice is based on the former ban and continues to fester within Mormonism because members are uncomfortable talking about it.

"I wish [LDS leaders] had more confidence in their doctrine and that the Holy Ghost testifies of truth. Black members could be presented the historic information and still choose to stay, like I did, because of all the good there is in the church. Truth will carry them through."

She bristles when LDS leaders point out how faithful African members are and wonder why African-Americans can't be like that.

In addition to being patronizing to Africans, Petit says, such statements imply Americans are "somehow inferior."

The differences between the groups of blacks is striking, says Darius Gray, one of the founders of the Genesis Group, a support organization for black Mormons.

"African nations were colonized by European countries but always the Africans were in the majority," says Gray, who worked briefly in Uganda. "After gaining independence, those new nations had black presidents, prime ministers, judiciaries, teachers, business owners."

When African Mormons move to Utah, however, they suddenly are in the minority and face the same obstacles as their American-born counterparts — and it's based solely on skin color.

Coming to America • Amram Musungu joined the LDS Church in 1992 as a 14-year-old living in Nairobi, Kenya, and within three years served a full-time mission in his homeland.

Now in Utah, Musungu is married with two children, works as an accountant, sings in the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and helps lead a burgeoning, 300-member Swahili ward in Salt Lake City.

He doesn't care about the former priesthood ban.

"Everyone asks why, why, why it didn't happen sooner," Musungu says. "We don't know. We are just rejoicing at our opportunity to hold the priesthood and bless the lives of our families."

Even Musungu, though, has experienced the sting of racist comments.

Once, when he was introduced as being a Mormon from Africa who sings in the choir, another church member asked: "What are you doing in our world?"

Stunned, the gentle African replied, "We are brothers and sisters, and this world belongs to all of us."

Many members of hisSwahili ward report what they perceive as job discrimination in the Beehive State, and indifference and even rudeness on the part of white Mormons, who share a building with them.

This saddens Musungu, who serves on his LDS stake's high council.

"If we fail to love each other based on [a foreign] culture, we are in a spiritual critical condition," he says. "The white race needs to embrace these new members. They are young in the gospel. We are all living the same gospel. How we get [to heaven] depends on how we treat each other in this life."

Clearly, such actions violate Mormon teachings.

"I am told that racial slurs and denigrating remarks are sometimes heard among us," Hinckley said during the all-male priesthood session of the church's General Conference in 2006. "I remind you that no man who makes disparaging remarks concerning those of another race can consider himself a true disciple of Christ. Nor can he consider himself to be in harmony with the teachings of the church of Christ."

But how to weed out such behavior?

A black face in the mirror • For some, including Paulette Payne, part of the answer could be "geography."

"I was reared in a military family and traveled a lot," she says. "There were times when I was the only black among Koreans, or some other racial group. That helped me to cope."

After Payne joined the LDS Church at 14 with her mom and sister in Augusta, Ga., being an African-American girl there was, well, "challenging," she says. At church dances, only one young man ever crossed the racial barrier and asked her to dance.

Still, she says, she learned much and truly loved the LDS youth program.

Now Payne attends an urban Atlanta ward, where black members make up half the congregation.

They have brought their religious culture from their previous faiths, she says, noting that the congregants call out their "Amens" during a speaker's talk or testimony.

Payne moved to Atlanta to study Africana Women's Studies in graduate school. She wrote her thesis on the black women in her ward and the strength they drew from their Mormon community.

She, too, believes the church should be more open about the priesthood ban, even discussing it with potential converts during missionary lessons. She would like to see more black faces — not just Africans — in church art and manuals. She hopes the story of courageous black Mormon pioneers such as Jane Manning James, Green Flake and Elijah Abel will become as well-known as the ill-fated Martin and Willie Handcart Companies.

Payne, a talk-show host, loves the idea of casting a black Adam and Eve in the LDS temple film, which tells the story of the creation and God's plans for his children.

"Every time I go to the temple, I try to focus on what I'm there for," she says. "But I don't find myself in the imagery."

On Saturday,Gray attended the annual Genesis Group picnic, celebrating the anniversary.

Participants had come from near and far, out of state and even out of the country, representing various racial and ethnic groups. Some were members, others were not.

"What struck me was the ease with which they interacted," he says. "There were no apparent differences. No 'red states,' no 'blue states' and none of the vitriolic language that has become so ever present. Kids played with kids as adults laughed, shared stories, danced and simply enjoyed one another's company."

Looking at that scene, Gray thought, "This is the way that God's family is supposed to act."

Mormons and race

Decades after Mormons lifted the ban on ordaining black men to the priesthood, racist attitudes linger within the LDS church. Trib Talk's Jennifer Napier-Pearce on Tuesday at 1 p.m. will speak with Marvin Perkins, Darron Smith and Max Mueller about the legacy of the priesthood ban and ways to improve Mormon race relations. Join the online video chat at sltrib.com.