This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When the U.S. Postal Service's first remote encoding center, or REC, opened in Salt Lake City in 1994, The Salt Lake Tribune reported that it was expected to operate for 10 years.

Within three years, USPS had opened 55 RECs, where workers rapidly assigned bar codes to images of handwritten and shoddily printed addresses that stumped the Postal Service's character readers. Those workers processed 19 billion images in 1997. But there was never any doubting the future of postal encoding: It belonged to the machines.

After the 54th REC closure in Wichita, Kansas, in 2013, that location's manager, Dennis Lyons, issued a frank eulogy. RECs such as his, he said in a news release, "were created and deployed with the knowledge that new technology would eventually eliminate the need for them."

Wichita's closure made Salt Lake City's REC not only the nation's first, but its last — the goal of the REC's leadership, ever aware of its mortality, when it opened in 1994.

Yet current employees say they don't expect it to shutter anytime soon. To the contrary, said manager Barbara Batin.

They're hiring.

Group leader Holli Apodaca, who started in 1997, once thought, "I hope I'll get my 20 years in," she said. "Now there's not a doubt in my mind."

The REC has changed since Apodaca signed on, lured from her customer service post at Packard Bell by competitive hourly pay and the promise of relief from impatient customers.

It then was housed in an annex by the airport, less than half the size of the current 77,000-square-foot office at 1275 S. 4800 West, and in those early years, the "keyers" had to physically move to terminals associated with a city.

Managers might have sounded like air-traffic controllers, keyers colliding between the rows of no-frills cubicles as they rushed to fill a need. Apodaca recalled with a laugh her confusion when she first heard the announcement: "If you're in Salt Lake, we need you to move to Albuquerque."

While the scene today might not strike a visitor as particularly high-tech — it looks and sounds like a never-ending, decades-old library computer lab — data now are pooled so a keyer at any one terminal can process images beamed in from around the nation.

Last year, the REC's more than 1,600 employees processed 2 billion images. Computers can read about 80 percent of packages and 99 percent of letters, but each Salt Lake City keyer still processes roughly 6,500 images per day.

Many worked 12 hours a day, six days a week, for almost a full month to meet the holiday demand, when volunteers were sought for 16-hour shifts.

It marked the second Christmas at the REC for Kearns' Miguel Vega, who began shortly before an especially overloaded 2014 holiday season. Vega said he is from Chile, where it is summer, and the time away from his family made him depressed.

But "I learned how to love this country," he said. "Once I [got] this job at USPS, I learned that I have a responsibility with the people."

Said Batin: "We're a single point of failure. If we go down, it affects the whole country."

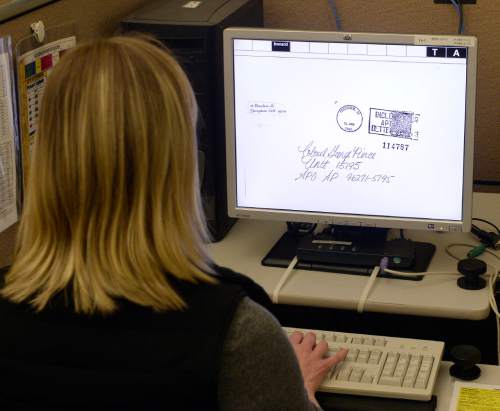

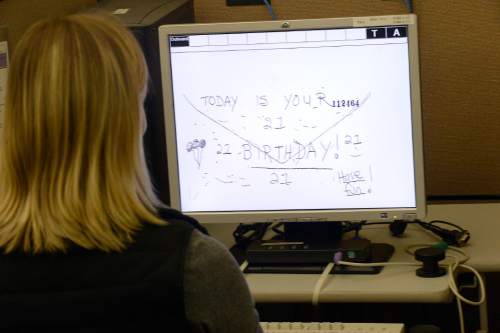

Keyers process parcels, flats and change-of-address forms, in addition to handwritten letters.

Images of the mail appear on their screens with a series of prompts. Keyers type in the missing pieces of the address using rules and shortcuts that minimize keystrokes. When they're done with one piece of mail — which they often are in little more than a second — the next pops up.

They're expected to meet a minimum of 7,150 keystrokes per hour without exceeding a 2 percent error rate. Ten seconds would be "a long time" to spend on a single piece of mail, Batin said, and while a keyer might deduce a scribble's meaning with a glance at the more legible writing, the REC doesn't encourage guesswork or delay.

If they can't read an address quickly, they reject it, and a seasoned clerk back at that mail's physical location might be able to determine the sender's intent.

Ironically, given that a keyer's reasoning skills are what distinguish him or her from the computers, the work can feel mindless. Some stand, and some bob their heads to music.

Said West Valley City's Jody Hurst, who's currently listening for the second time to the audiobook "Grass for His Pillow," by Lian Hearn: "Keying here, honestly, I don't think I could make it through the day without something to listen to."

Clearfield's Kelley Murray, who started in 1996, said they used to be allowed to talk while they keyed, but that was seen as a detriment to productivity. Now she's hooked on audiobooks, most recently "Me and Earl and the Dying Girl."

The privilege of wearing headphones comes only after employees have passed a series of tests — they have 55 hours to do so — and completed a 90-day probation period.

The tests can be challenging, and the training software is about as cutting edge as you'd expect, given that the REC has been in a constant state of thinking it soon might closed.

Some of the older prospective keyers are less comfortable with a keyboard, Apodaca said. Younger keyers often struggle to read cursive, and one blamed the loopy script when he quit last month on his second day.

The center loses about 70 employees each month, Batin said.

Murray joked that she should get overtime for the address labels she sometimes sees in her sleep. But she and others said they were proud to be part of the last, and therefore best, REC. For Hurst, a group leader who first was assigned to images sent in from the Seattle plant when the Salt Lake City REC opened in 1994, it will be a treat to finally visit the Emerald City this June, armed with an unnatural knowledge of the area's ZIP codes.

Batin said few countries use RECs. Representatives from Canada once visited to learn the method and decided it wasn't for them, she said, opting instead to require customers to print their addresses.

She hopes the USPS never goes that route. "It's Grandma's letter that was sent to little Billy," Batin said, "and maybe Grandma, in a couple of years, isn't around anymore, and to have a handwritten letter means more than something that was typed."

Batin said the REC plans to hire as many as 500 new employees. Those interested can apply at USPS.com.

Twitter: @matthew_piper