This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note: This is one in a series of profiles of members of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah. Find the full story here.

Flowers still adorn the grave of Joe Levi.

The letters scratched on his headstone —

B

JOE LEVI

d/7/19

— show he died long before any present-day Kanosh Band members were born. But fabric lilies, daisies and sunflowers cover his burial site. It's a gentle mark of ownership, left by Levi's descendants on a small cemetery that they no longer actually possess.

The band's traditional burial site sits just outside the boundary of its tiny reservation.

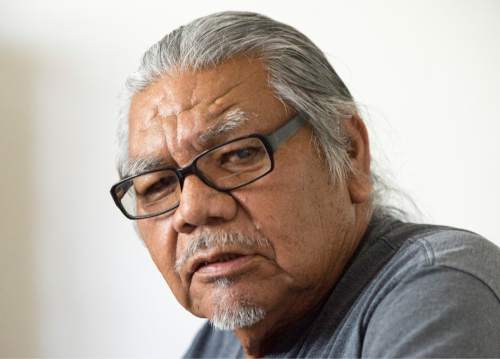

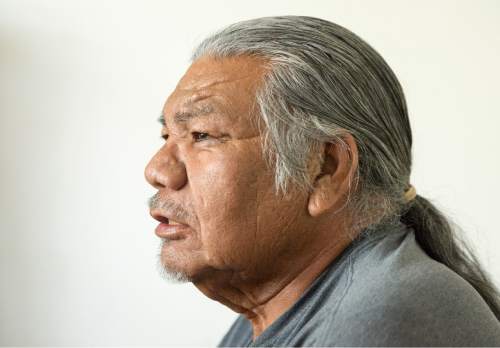

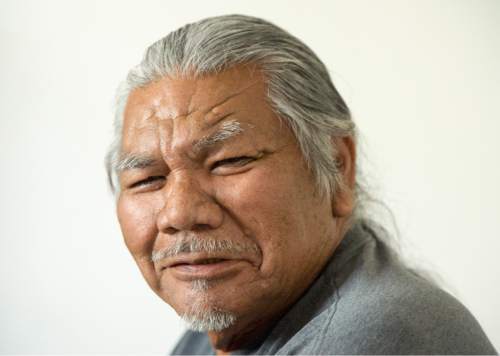

Phil Pikyavit, a tall 74-year-old with a long, salt-and-pepper ponytail, lingers over the graves of his parents. Emily and Joseph Pikyavit raised him across the street from the cemetery in the Kanosh "Indian Village," as it's labeled on maps. It has been Pikyavit's home for nearly all his life. A dozen houses and trailers stand along a single road in a broad, flat stretch of scrub at the foot of the Pahvant Mountain Range in Millard County.

When Pikyavit was a child, his parents built a shack out of railroad ties for their nine children. Extended family eventually filled up the space. Pikyavit recalls sleeping most summer nights on the grass outside; in winter, he and his brothers slept in a tent on a wooden platform.

"Every morning we had to thaw the water out so we could wash our faces," he says. Pikyavit, like many in the Paiute tribe, would not have in-home electricity or plumbing until the 1970s.

Pikyavit grew up speaking Ute. The Kanosh Band, though now considered Paiute, descends from a Ute band whose leader refused to join others on reservations in the Uintah Basin in the late 1800s. He opted instead to keep the band near its traditional fishing, hunting and foraging spots throughout eastern Millard County — and, importantly, its farms in fertile valleys around Corn Creek.

That leader, Chief Kanosh, is best known in non-Paiute history as the first American Indian to be baptized into the Mormon church. His Wikipedia entry, attributed mostly to church-related sources, states that Chief Kanosh "invited the Mormons to come and settle in his area where they founded the town of Kanosh."

That's not how the band sees it.

"When Mormons came, they found it was good land," Pikyavit says. "They ended up with that and pushed us up here on the rocks."

The band and the church have a complex shared history that sidestepped warfare in favor of a strategic alliance, but often pitted the interests of each in a competition the band could not hope to win. With settlers controlling nearly all of the water and productive land, the Kanosh people moved to the Indian Village.

After Congress terminated federal recognition of Utah's Paiutes in the 1950s, most of the Kanosh reservation lands were lost. A number of children were channeled into the Indian Placement Program of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which moved children from reservations into white, LDS families during school years. Pikyavit says the program is a big part of the reason why he is one of only a few remaining Kanosh members who can speak the band's traditional Numic language, considered by linguists to be "severely endangered."

"The church took all these kids into custody and took them up there so the whites can raise them, and then they forget about the language," Pikyavit says.

His own son went to another family, but only briefly.

"We let the church take him for about a half a year," Pikyavit recalls. "Then we decided to go and get him back because we couldn't have him staying there and us staying over here."

The band got some of its land back, too, with the 1980 restoration. But the new Kanosh reservation was less than half of its old size. And it did not include the cemetery.

"I'd like to get that land and put it under the trust for the Kanosh Band and put it on the National Register [of Historic Places]," says Pikyavit, who is the band's chairman.

For now, the band remains at the mercy of private landowners to pay their respects to Levi and others: Emily and Joseph Pikyavit. Andrew Huncup, who died May 10, 1918. Pikyavit's grandson, Michael. Ruth Timican, whose faded original headstone — a red rock with eagle feathers carved into it — was replaced with a modern marker honoring "nani pian" — Paiute for "my dear mother." A child identified on a marker only as "Girl, 1917."

And untold others, whose graves aren't marked but who the band believes are there, nearby but not quite home.