The slurs came at the young boy like barbs.

Sometimes the word hurled his way from other kids was “guera,” meaning “girl” in the dialect of his native Ugandan village. At other times, it was “mudiga,” a word used for gay people, he said.

“I used to talk like a girl … walk like a girl. I used to be in the company of girls, so they called me all sorts of names, because I was expressing like a girl,” said Barnabas Wobiliya, 36, who remembers being about 10 when the teasing began.

Apollo Kimuli tells a similar story of his childhood.

“Chimmalgi. That’s what they used to call me,” the slight, lanky 28-year-old said. “It means flower.”

These words left a lingering sting for these young men struggling to understand the feelings they held for other boys.

The road ahead, however, would bring things far harder and crueler than words.

As adult activists promoting LGBTQ rights and HIV/AIDS treatments, the two were repeatedly beaten, arrested and jailed, before finally, fearing for their lives, they fled Uganda, to seek safety and asylum — a quest that led first to Kenya and then, in 2016, to Utah as refugees.

Here, they are trying to build new lives, while continuing their shared mission to help the LGBTQ community at home in Africa.

Uganda is one of more than 30 African nations with anti-homosexuality laws. Just being gay is illegal and can send you to prison for seven years. It’s also a crime to advocate for gay causes or to fail to report a gay person to authorities.

Culturally, the south-central African nation — which is tucked between the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west and Kenya to the east — is also a religiously conservative place, so the deck is twice-stacked against LGBTQ citizens.

A 2016 report by the U.S. State Department criticized Uganda for its human- and civil-rights failures, including violence and discrimination against women, children and other marginalized groups, including the LGBTQ community.

Activism around gay rights or gay causes is a dangerous and sometimes deadly occupation. Violence is not uncommon and many have died fighting against the country’s oppressive, discriminatory policies.

Despite those risks, Wobiliya and Kimuli were driven to put their names and faces to the cause in hopes of saving the lives of gay Ugandans who were dying from AIDS.

“Activism is like a spirit,” Kimuli said. “The moment I came out in the media, I never thought of [the risk]. I was beaten, arrested I don’t know how many times, but I couldn’t care.”

Wobiliya and Kimuli, who are not, nor have ever been, a couple, became friends through their work.

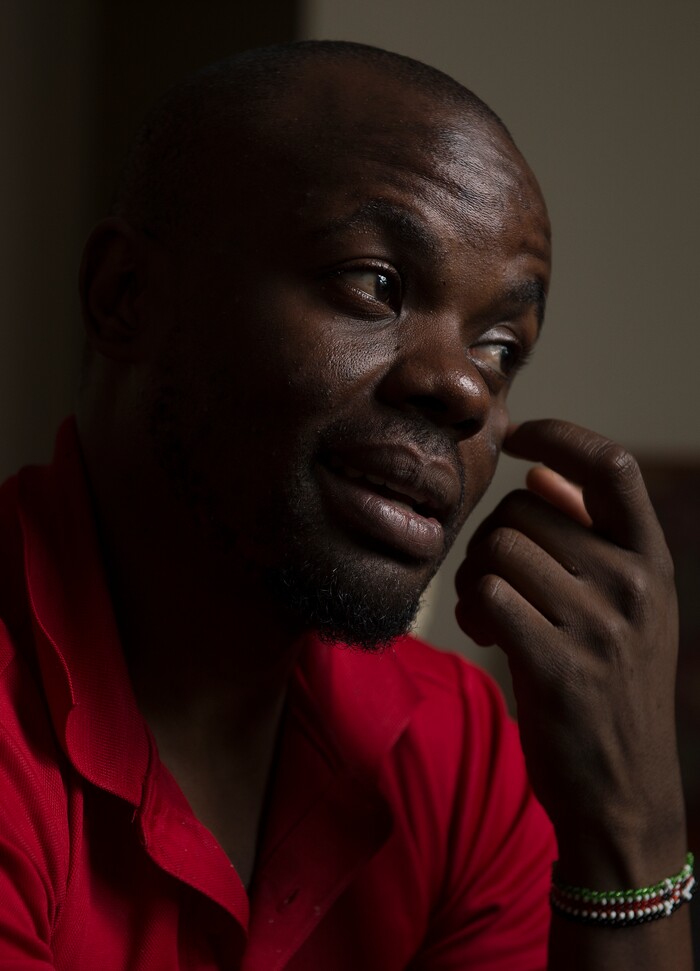

(Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune) In his native Uganda, a place where being gay can send you to prison, Barnabas Wobiliya risked his life as an advocate for AIDS education and equality for the LGBTQ community. Threatened with death, he fled and spent a year in refugee camps before resettlement in Utah. Wobiliya is using the Internet to continue his activism for others in Africa's LGBTQ community.

Wobiliya grew up in a village in the rural Sironko district of eastern Uganda, which touches the border with Kenya and is north of Mbale, where Kimuli’s family lived.

Harassment was a daily part of life, Wobiliya said, and its source wasn’t always limited to other kids.

His own parents would often beat him, Wobiliya said, especially if they discovered him dressed up in his sister’s clothing as he often did after school. There was no one to turn to for help, he said.

“I was, like, outcast. I almost committed suicide,” Wobiliya said. “And because I had the mentality of a village man, I thought this is abnormal.”

By his mid-20s, he was studying business at the Uganda College of Commerce, living with a woman with whom he had an infant son, named Elvis. The relationship didn’t last, said Wobiliya, who then began to embrace and understand that he had always been gay.

Advocating for HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment became an easy career choice. Four of Wobiliya’s 14 siblings died from HIV/AIDS-realted diseases or health complications.

None had taken preventive steps against infection, nor sought treatment once ill, he said.

“I could not watch them die,” he said.

In 2009, Wobiliya helped found Hope Mbale, an organization to connect people with HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment services.

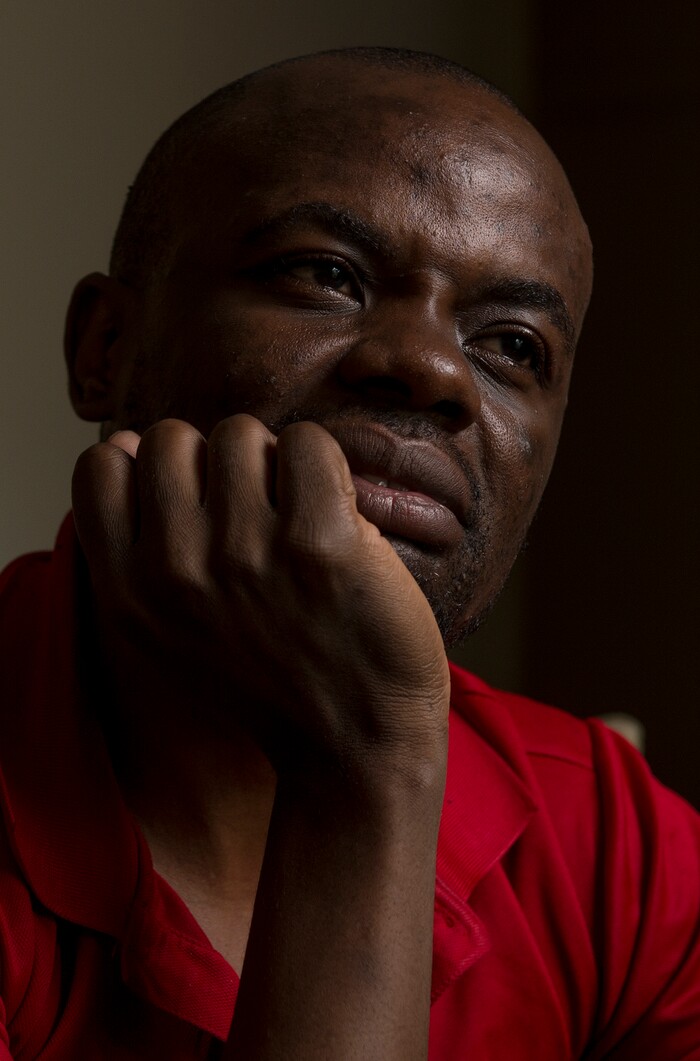

(Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune) In his native Uganda, a place where being gay can send you to prison, Appollo Kimuli risked his life as an advocate for AIDS education and equality for the LGBTQ community. Threatened with death, he fled and spent a year in refugee camps before resettlement in Utah. Kimuli is using the Internet to continue his activism for others in Africa's LGBTQ community.

Kimuli grew up with three sisters in a Mbale household headed by his single mother, a politically active and locally famous feminist who had outlived her polygamist husband.

Like Wobiliya, Kimuli said he understood that the words others slung at him were meant to disparage and insult gays, but he couldn’t make a connection between the words and the questions he had about himself.

At 15, he said, he was targeted and raped by an older man, who was the uncle of a friend. He kept the painful assault to himself until age 18, when he finally told his mother.

“I was lucky I didn’t get HIV,” he said.

As a student at Kampala International University in Uganda’s capital, he went in search of someone to help him talk through the experience. Using a fake name to protect his identity, Kimuli got on Facebook and met his first boyfriend.

“That guy made me to feel like, ‘Yeah, the world was in my hands,’” Kimuli said.

Kimuli’s activism started with the formation of an online group to connect LGBTQ students to one another. Kuchu Love Uganda, which later became Kampus Liberty, wasn’t recognized by the school — that would have been illegal — but it began to create a much-needed community of support for students who lived their lives mostly in secret.

Later, fueled by his own rape experience and a move by the Ugandan government to ban access to HIV/AIDS drugs, Kimuli sought training as a health worker.

“I felt we needed to advocate for HIV because gay people are most at risk,” he said. “If there continued to be no access to treatment, we would all die.”

It was while working with the Most At Risk Populations Initiative, which provided HIV testing and other resources to gay men and sex workers, that he met Wobiliya. The two attended the same training workshop in 2012, and later forged a friendship as their paths crossed again and again in the community.

Kimuli, who also worked sewing women’s fashions and braiding hair, came out publicly that same year. It prompted a backlash from his otherwise supportive mother. Frightened for her own reputation, she told him to visit only at night when the neighbors might not notice him and to come by motorcycle so he could make a quick escape if needed.

He was, he said, beaten and arrested for being the public face of gay rights, but didn’t waver.

“My mom motivated me. I was like, ‘If she can do it as a woman, then I can make it,’” he said. “I knew that out of pain there would be gains.”

But by 2014 Uganda reached an anti-gay fever pitch.

The country’s Parliament had passed so-called “Kill the Gays” legislation, which imposed a death sentence on anyone convicted of having “carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature.”

Activists organized and protested. There were arrests and beatings that left more than one activist dead.

Kimuli was swept up by police at a protest outside a gay club. He spent three days in jail, enduring deplorable treatment and conditions. On each day behind bars, the charges against him changed, he said. First it was “unnatural offense,” later “inciting violence.”

A human-rights group finally arranged for his release on bond.

Even as the dangers increased, the two men said, they kept up their work.

“We say it’s too risky not to do it,” said Kimuli. “Because it’s a calling within us. We have to keep advocating or the work is not going to go on.”

In 2015, however, the dangers changed. Homophobia and violence had increased and the emotional tolls intensified.

Wobiliya was reported to police and evicted three times by landlords who questioned whether he was infected with AIDS and feared their own arrest.

He said he was also tossed out of church in the middle of a service while singing with the choir. The pastor said gay people could not be accepted.

“The major thing that made me move was fear of persecution,” he said. “I was rejected most places.”

Around the same time, Kimuli was stopped by police while driving home to Mbale from a workshop in Entebbe. The officers beat him badly, he said, which drove him to start thinking about how to find a more peaceful existence.

“I was like, ‘I think enough is enough,’” he said. ‘“I’m done.’”

Then a neighbor called to tell him not to come home: Police were ransacking his apartment and looking to arrest him.

Kimuli called an attorney for help and was advised to flee and seek asylum. Otherwise, the lawyer suggested, “you’re going to die,” Kimuli said.

Without a wallet, money or a travel visa, he fled to Kenya with just the clothes on his back, hoping he would be allowed to cross the border with only his passport.

Whether by accident or fate, Kimuli and Wobiliya unexpectedly crossed paths at a United Nations refugee center in Nairobi, where both registered for asylum.

While they waited for news of resettlement, the friends got jobs that allowed them to continue to work as advocates and earn enough to stay out of the crowded camps where most refugees lived.

Kimuli was elected to represent LGBTQ individuals in the refugee community and secured funding for gay men sick with HIV/AIDS-related illnesses or tuberculosis. Wobiliya worked as an HIV/AIDS outreach coordinator.

Within 15 months, both men were approved for resettlement and left Kenya for the United States.

They arrived in Salt Lake City within days of each other in late September and early October 2016. They are among only a handful of refugees to come to Utah who have identified as openly gay, the local office of the International Rescue Committee said.

Today, they are roommates in a northwest Salt Lake City apartment stocked with hand-me-down furniture and kitchen goods and other amenities secured through the help of local LGBTQ activists and the Mama Dragons group of Mormon women who advocate for gay kids.

The two refugees’ beginnings here were bumpy. Language barriers, cultural differences and winter weather all made for adjustments that could throw anyone, said Connell O’Donovan, a local activist who met them through a Facebook message and introduced them to Equality Utah and the Utah Pride Center.

“They are thriving,” he said. “They hit the ground running, have made many friends.”

On its face, the men say, Utah is a better and safer place than Uganda, or even Kenya, but it’s not without challenges.

Utah, is after all, the heart of the conservative Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and mostly white, which gave both some trepidation about settling here.

In addition, they say, the cost of living here is high compared to Uganda and the wages both earn from selling electronics and travel supplies at Salt Lake City International Airport are low. After rent and other expenses, they say, it’s hard to save or set aside any money to send back to the LGBTQ community in Africa.

These days, the two — who both want to study to become nurses — are continuing their activism online. They’re focused primarily on providing financial help to LGBTQ youths in Nairobi.

“This is more frustrating because you are far away,” said Kimuli. “You can’t do as much if you are not on the ground.”

This fall, just before the anniversary of their arrival in the Beehive State, Equality Utah honored the men with a “fighting spirit” award during its annual fundraising dinner. The honor is a nod to the suffering and sacrifices Wobiliya and Kimuli endured and their unwavering commitment to continuing to work to improve the lives of LGBTQ Ugandans, Troy Williams, Equality Utah’s director, said.

“It’s one thing to be an activist in Salt Lake City and know that if I’m arrested for something, I’m going to be out of jail at the end of the day,” said Williams. “For them, it’s a very different story. They risked their lives to advocate for people with HIV. That kind of courage, to me, is astonishing.”