A franchise system, similar to that used by fast-food restaurants, distributes Mexican black tar heroin in Salt Lake City’s troubled Rio Grande district, presenting a formidable challenge to law enforcement’s efforts to clean up the area.

In many U.S. cities, including Utah’s capital, individual Mexican traffickers set up decentralized organizations created to keep authorities from stemming the rising tide of the relatively cheap drug, according to journalist Sam Quinones, who extensively researched heroin trafficking and its link to pharmaceutical opiate addiction.

The heroin flows from the feared Sinaloa Cartel through legal entry points in the U.S. and on to Salt Lake City, where the franchise holder breaks it down into individual doses for distribution, he told The Salt Lake Tribune.

It is then delivered by couriers who most likely aren’t acquainted with the man for whom they are working. They are usually impoverished young men seeking a better life. And when one is arrested and deported, more are waiting to come north to cash in on the drug trade.

In his book, “Dreamland: The True Tale of America‘s Opiate Epidemic,” Quinones outlined a system, much like Pizza Hut, that makes buying heroin more convenient and less expensive for addicts than ever. Call in an order, and they’ll bring it to your doorstep.

Mexican heroin traffickers figured out how to make their product affordable — about $15 per dose, similar to the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, when dealers found that by cooking cocaine with baking soda, it went further and could be sold for $10 a hit.

The growing market for black tar is tied to people from all walks of life who become addicted to pharmaceutical painkillers, either prescribed or obtained on the black market. Eventually, that leads many to Rio Grande Street and 500 West looking for a cheaper fix.

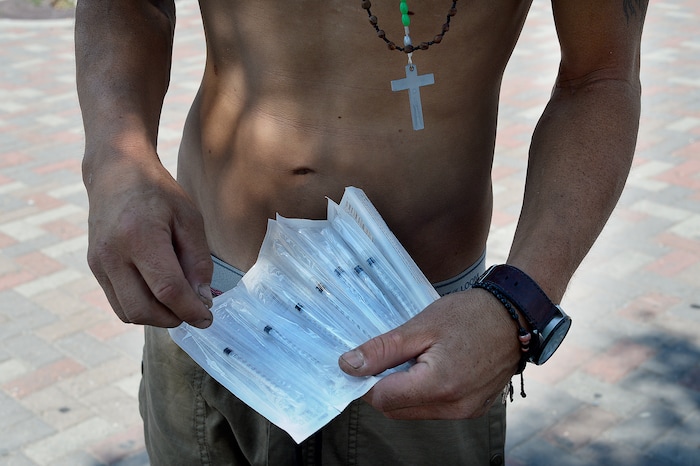

Black tar heroin has the consistency of a Tootsie Roll. A 1/10 gram dose looks like a small M&M. Addicts dissolve it with water in a bottle cap and then suck it up into a syringe.

Many heroin users in the Rio Grande area seem like zombies — either passed out or looking feverishly for their next dose. The addiction dominates everything, leaving many users with little beyond the clothes on their backs.

Heroin will be a problem, said Salt Lake City police Detective Greg Wilking, as long as opioids are available.

Some 80 percent of heroin addicts first became dependent on painkilling pills, according to the Utah Department of Health.

“It‘s supply and demand,” Wilking said of heroin trafficking. “As long as there is a demand, the drug dealers will find a way to get it to them.”

Utah Gov. Gary Herbert, along with legislative and municipal leaders, has launched ”Operation Rio Grande,” a new strategy to mitigate the chaos and lawlessness on the western edge of downtown. It entails a greater police presence, more arrests and the promise of additional mental health and drug treatment resources.

But reclaiming Rio Grande appears to be a daunting task, by anyone’s measure. Denver may provide a cautionary tale.

In August 2016, Denver law enforcement officials, along with agents of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, culminated Operation Muchas Pacas, a yearlong drug interdiction effort. According to The Denver Post, it netted 25 criminal indictments, 47 pounds of heroin and $218,000 in cash.

But a year later, little has changed on the streets of the Mile High City — addicts continue to have easy access to Mexican heroin and can be found sprawled out around downtown, according to The Post.

In Salt Lake City, stepped-up efforts in Rio Grande have yielded increased seizures of illegal drugs. According to police stats, more than 189,000 doses of drugs valued at $1.5 million were seized in the area in 2016 — a jump of 58 percent over 2015. But there remains no shortage of heroin on the streets, according to patrol officers.

The large quantity of Mexican black tar heroin coming into the U.S. and Utah — along with its profitability — will continue to challenge law enforcement.

Black tar heroin has become an enterprise worth hundreds of millions of dollars per year. One kilogram yields 10,000 doses, which are sold at roughly $15 each. That’s a total of $150,000.

And there is no shortage on the production end. Heroin poppies grow in the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre del Sur for hundreds of miles near Mexico’s west coast from Chihuahua to Oaxaca, Quinones explained. Black tar heroin is less refined than heroin coming from the Middle East or Afghanistan and much easier and less expensive to produce.

It also has more impurities. According to DEA data, overdose deaths have increased along with the influx of black tar heroin during the past seven years.

Salt Lake City used to be a point of transfer for drugs headed elsewhere, said Sgt. Chad Jensen, Utah Department of Public Safety. But now, Utah’s capital is a known market and heroin is coming largely through the highways.

It comes in cars, trucks and buses. Passengers will tape chunks of black tar to their legs. The stream of small packages of five to 13 pounds is endless, Jensen said. (One kilogram is equivalent to 2.2 pounds.)

Drug franchise holders use runners with cars and cellphones and do a thriving business in cities and suburbs. But downtown areas, like the Rio Grande district, tend to be the targets of Honduran drug runners, who specialize in walk-up trading, Quinones noted. They sell mostly to junkies.

Salt Lake City police say that most of the dealers they arrest around Rio Grande Street and 500 West are from Honduras. But they are the little fish, not the franchise holders. As soon as one runner is arrested, there is another to take his place, said police Sgt. Sam Wolf, who patrols the area.

Because the couriers don’t know whom they are working for, they can’t give them up to investigators. And the Mexican black tar heroin keeps coming.