This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Hearing about military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder raised personal questions for Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey some 50 years after the Salt Lake City artist had been interned with her family in Colorado's Amache Relocation Center.

Memories of her girlhood in the camps were mostly long buried, but she began to wonder about the floating anxiety she sometimes felt. Once she was watching a TV show where two women heard a loud sound; one startled and one didn't. Loud sounds made Havey uneasy, and watching a character sit calmly despite a startling sound just didn't seem normal to her.

Havey, a mother of two sons, is a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music, a former English teacher at Skyline and Cottonwood high schools who went on to establish a stained-glass studio.

In the 1990s, considering how soldiers with PTSD were advised to re-create the sounds and smells of their trauma, Havey turned to painting. She eventually created a gallery's worth of watercolor works, inspired by her memories of her childhood at Amache. "I didn't start painting until I was 65," says the 82-year-old artist. "Sort of like Grandma Moses."

The haunting paintings didn't have messages, but were instead intended as a way to relieve Havey of her long-held feelings. When she exhibited her paintings at museums or galleries, curators would ask her to write blurbs to explain the scenes. The artist would write the sentence or two, as requested, but then she couldn't stop. "There was too much to write about," she says. "My feeling was that there was more to say."

To write, she would go into her head as if she were seeing her childhood through a movie camera, as if she were still a 10-year-old sitting on her father's suitcase, waiting to go camping.

She remembers her disappointment when she learned she wasn't going fishing with her brother and her often-distant father, but instead was billeted first at the Santa Anita Racetrack, and then in hastily built barracks in Colorado that looked as if they were covered in sandpaper. The family would never return home to California. "I remember so much about those four years," Havey says. "I don't remember subsequent years as vividly as I do those years in the camp."

Eventually, she stitched together the movie scenes of her memories, as well as the family stories she learned while working with her mother, a seamstress.

Her internment-camp coming-of-age memoir, "Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp: A Nisei Youth Behind a World War II Fence," was published this summer by the University of Utah Press. The story of "Gasa Gasa Girl," the term her mother used to describe the young girl's bold restlessness, unfolds in a beautiful hardcover volume that includes vintage photographs as well as Havey's artwork.

"Sharing my stories and showing my paintings have built a sense of lightness and freedom," Havey writes in the preface.

What sets apart this creative work is the young narrator's curious voice, which also seamlessly incorporates the writer's Grandma Moses wisdom. Readers term the writer's voice "engaging." "She puts you back in that world view as an adolescent," which adds immediacy, says John R. Alley, editor in chief of the U. press.

"In the summer of 1942, everything ended, and nothing seemed to begin," Havey writes in "Gasa Gasa Girl." "August was scorching. The sun blazed off the asphalt and roasted the elevated barracks. Inside them felt like a baking oven."

Young women eagerly volunteered to construct camouflage nets for the U.S. Army. "The irony of this scene dawned on me years later," Havey writes. "At Santa Anita, I was bewitched by these nets and saw only gorgeous colors and shapes. In reality these women were creating disguises of green and brown for men who were sent to destroy my relatives."

She successfully captures not just the heartache of the Americans forced to leave their West Coast homes and their lives, but the way they made do in the camps, attempting to practice gaman, the Japanese notion of enduring challenges with patience and dignity.

The story gracefully blends its dark history with a kind of light-hearted girlish mischievousness, told by an adolescent still dreaming of developing breasts who learns she's allergic to wool only after she gets her period and straps on a woolen pad holder.

"She really gets us inside these camps, and helps us understand how awful it was, with a child's perspective that makes it really interesting," says Betsy Burton, owner of The King's English Bookshop.

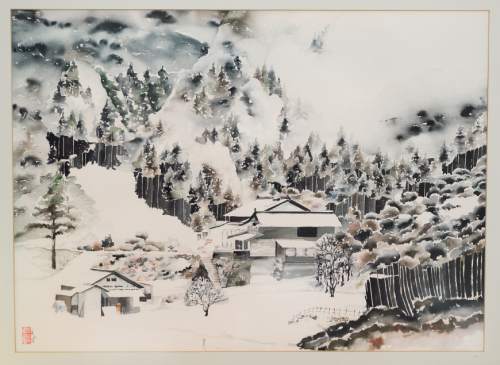

Coupled with her poetic storytelling are the layers of emotion added by Havey's paintings. That's evident in one of her most recent works, which she donated to the Amache Preservation Society this spring along with a copy of her book.

Havey says she's returned to the interment site five times, including the most recent pilgrimage to see a re-creation of the orange-and-white checkered water tower, which was much taller and bigger than she remembered.

"Wild sunflowers were dug up and cultivated by some evacuees to adorn the bleak surroundings," she writes in the painting's caption. "Mostly we looked out on cacti and sagebrush. The tiny line of barracks covered with snow are overshadowed by these golden flowers. But no matter how we decorated our grounds, we were still surrounded by barbed wire. The orange-and-white checkered water tower supplied the water to feed us and the flowers."

Burton points to a haunting painting in the book, "The Lights Searching," which depicts a young girl making her way to the bathroom while a guard shines a searchlight on her. "I thought he might kill me," Havey writes in the caption. Years later, her husband suggested that the guard might have been trying to protect her by lighting her way. —

'Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp'

Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey will read from her memoir.

When • Wednesday, Oct. 29, 6 p.m.

Where • Okazaki Community Meeting Room (Room 155) at the University of Utah College of Social Work, 395 S. 1500 East, Salt Lake City